Grassroots network of researchers and frontline medical workers publicizes hard data on the ongoing coronavirus crisis; encourages political activism for science-based public health policy

Jason Pramas

A Home in the Digital World

science

IN 2022, GIVE SCIENTISTS SOME LOVE

We can criticize the institutions that employ them without dismissing their vital work

IN 2022, GIVE SCIENTISTS SOME LOVE

We can criticize the institutions that employ them without dismissing their vital work

EDITORIAL: DIGBOSTON JOINS MOVEMENT TO SLOW GLOBAL WARMING

Calls for regional consortium of news outlets to improve and expand climate change coverage

Last month, during the fearsome heat wave that saw Boston temperatures soar to 98 degrees Fahrenheit for two days in a row, 400 chickens died in New Hampshire.

According to the Boston Globe, they succumbed to “heatstroke at Vernon Family Farm in Newfields, N.H., around 5 p.m. Saturday when the temperature peaked and the farm could not save them…” The article went on to explain that temperatures got up to 90 degrees in Newfields that day. But chickens cannot take heat over 106 degrees. And, despite the best efforts of the farm staff to keep them cool, the birds expired.

A New Hampshire Union Leader article provided more detail. Farm owner Jeremiah Vernon said that the heat index (a measure of how hot it really feels when relative humidity is factored in with the actual air temperature) on his farm just after 5 p.m. on July 20 when the chickens died was over 110 degrees—and added that another southern NH farm lost 300 chickens the same day. He also mentioned that “the farm has spent about $2,000 to buy generators and circulation fans to help prevent illness in the event of another summer heat wave.” Something he had obviously never had to consider over the farm’s previous 10 years of operation. Several of which were each the hottest years on record in turn worldwide.

As 2018 was. And 2019 may be. June was the hottest month on record. And then July was, too. Global average temperatures are continuing to climb. Month by month. Year by year. There is some fluctuation. Some cooler months and years. But only cooler relative to the ever-hotter new normal. The general trend is upward. And the speed of that climb is accelerating.

Even so, the death of hundreds of chickens from overheating was an unusual enough occurrence to be worth reporting in major New England newspapers. But apparently not alarming enough to mention the role that global warming is playing in increasing the number and severity of hot days summer by summer. Despite happening in the same month that the Union of Concerned Scientists issued a report, “Killer Heat in the United States: Climate Choices and the Future of Dangerously Hot Days.” Which used the best available scientific data to make the following predictions for New Hampshire:

Historically, there have been three days per year on average with a heat index above 90 degrees Fahrenheit. This would increase to 23 days per year on average by midcentury and 49 by the century’s end. Limiting warming to 2 degrees Celsius [3.6 degrees Fahrenheit] above pre-industrial levels could reduce the frequency of such days to 17 per year on average.

By the end of the century, an estimated 970,000 people would be exposed to a heat index above 90 degrees Fahrenheit for the equivalent of two months or more per year. By limiting warming to 2 degrees Celsius, all residents would avoid such days of extreme conditions.

Historically, there have been zero days per year on average with a heat index above 100 degrees Fahrenheit. This would increase to six days per year on average by midcentury and 19 by the century’s end. Of the cities with a population of 50,000 or more in the state, Dover and Nashua would experience the highest frequency of these days. Limiting warming to 2 degrees Celsius above pre-industrial levels would cap the frequency of such days at two per year on average.

Both the Globe and the Union Leader wrote articles highlighting the report’s findings, to their credit. But neither article echoed the Union of Concerned Scientists’ oft-repeated point that only limiting temperature rise 2 degrees Celsius above pre-industrial levels can prevent such calamitous outcomes. And neither publication mentioned global warming as a likely causal factor in the death of the chickens—given that the heat index got up to 110 degrees Fahrenheit the day the doomed birds perished—in their coverage of that story. Even though the UCS report states that the historic average number of days with a heat index over 100 in New Hampshire is “zero.”

This year there was at least one such day. So that isn’t normal. And although it’s difficult to peg particular weather events to global warming, it is thus definitely worth mentioning the strong possibility of a connection in this case. For a very good reason beyond the importance of keeping the societal discussion of global warming going hereabouts: The birds’ deaths add to a growing mountain of evidence that global warming is already beginning to threaten food production.

Like it or not, chickens are an important part of our food supply. But increasingly severe weather caused by a swiftly-heating planet is triggering major floods, major droughts, devastating wind storms, vast wildfires, and the spread of once-tropical insects and diseases—all of which harm crops and food animals, and put our future food security at risk. As sea level rise is starting to impinge on growing lands in low-lying areas. Making the NH chickens the equivalent of canaries in a coal mine when it comes to warning us of the looming danger to planetary food supplies—and highlighting a major problem with allowing average temperatures to continue spiraling skyward.

However, the planet is not getting hotter on its own. It is heating up because governments and major corporations are allowing the amount of carbon that human civilization is burning in the form of oil, gas, and coal to continue to increase. Putting more and more carbon dioxide—the main greenhouse gas—into the atmosphere every year. Despite those same governments and corporations paying lip service to the importance of decreasing the amount of carbon we burn. While the scientific consensus is now agreeing that the only way for our civilization—and perhaps humanity itself—to survive the rolling apocalypse that is human-induced global warming is to bring the net amount of carbon emissions (after somehow deploying carbon capture technologies on an industrial scale) to zero by 2030. A mere decade hence.

Yet in June, Bloomberg reported that “Global carbon emissions jumped the most in seven years in 2018 as energy demand surged, according to BP’s annual review of world energy…” So even huge climate criminal multinationals are aware that carbon emissions have continued to climb unabated—except for a short period after the 2008 financial collapse when manufacturing and transport slowed for a time across the globe.

All of which is to say that journalists need to do a much better job of covering global warming and its many dangerous effects. Too many stories like the sad premature death of the NH chickens do relate to climate change. But that critical angle too often goes unmentioned. And people then go about their daily lives thinking that global warming is something that will only affect humans in the far future or not at all.

WBUR just ran an interesting story on a network of major news outlets in Florida—a traditionally conservative state gradually coming to a political consensus that climate change is real—that have committed to collaborative coverage of the very obvious and constant effects of global warming in that low-lying subtropical farm state. Reporters and editors at those operations have decided that it’s their responsibility to work together to give this most dangerous of crises the constant attention it deserves.

And that’s clearly something that we need to do here in New England.

Especially in the Bay State, where the Union of Concerned Scientists projections are even more dire: “Historically, the heat index has topped 90 degrees in Massachusetts seven days a year, on average.” But if there is no global action to significantly lower carbon emissions, that number would increase to “an average of 33 days per year by mid-century and 62 by century’s end.” Furthermore, the Commonwealth “currently averages no days when the heat index tops 100 degrees,” but without changes to global emissions that figure would rise to “10 days by mid-century and 26 days by century’s end.”

So I’m writing to commit DigBoston to three things.

First, this publication is going on record in joining the environmental movement aimed at slowing human-induced global warming—stopping it no longer being possible. My colleagues and I accept the overwhelming scientific consensus that climate change is a terminal threat to Earth’s biosphere and to our species.

Second, we will strive to run more and better coverage of global warming in our own pages. And we will do everything we can to provide regular information on ways people can join together to build the movement to mitigate it.

Third, we are declaring our desire to help start a consortium of news outlets interested in working collectively to improve and expand coverage of global warming in New England. Alternatively, we will happily join an existing effort along those lines, should one we’re unaware of be underway.

Environmental journalists interested in writing for us—and environmental activists and organizations that wish to submit op-eds—are invited to email Chris Faraone and me with pitches at editorial@digboston.com.

And editors, publishers, and producers of news outlets interested in starting talks aimed at creating a reporting consortium on global warming in New England are strongly encouraged to contact us at the same email address.

We’re all overdue to take such steps. But journalists in the northeastern US can help change a lot more hearts and minds about the need to make slowing climate change a societal priority, if we work together.

Jason Pramas is executive editor and associate publisher of DigBoston.

FROM INJURY TO ACTION: A LABOR DAY REMEMBRANCE (PART III)

October 10, 2018

BY JASON PRAMAS @JASONPRAMAS

In parts one (DigBoston, Vol. 20, Iss. 36, p. 6) and two (DigBoston, Vol. 20, Iss. 40, p. 6), I discussed how working a temp factory job at Belden Electronics on assignment for Manpower for several weeks in early 1989 in Vermont led to my sustaining a sudden and permanent spinal injury while walking to my car just after my last shift. And how I drove myself one-handed through a snowstorm on country roads in the middle of the night to an emergency room—only to receive substandard care as a poor person. Leading me to make the mistake of letting cheaper chiropractors hurt me more over the next six years. In this final installment, I review my turn to labor activism on behalf of myself… and workers in bad jobs everywhere.

I recovered from my spinal injury within a few months. To the point where I wasn’t hurting all of the time. Just some of the time. Yet, as with other life-changing experiences before and since, I wasn’t the same afterward. Physically or psychologically. I was left with the sense that anything could happen to me at any time. Something I had known intellectually before getting hurt, but literally knew in my bones going forward.

Regardless, once it was clear I wasn’t going to be entirely disabled, I resolved to move ahead with my life. Which took some time. But by the summer of 1990, I had returned to Boston from Vermont, I was dating the woman who later became my wife, and I had founded New Liberation News Service (NLNS)—the international wire I would run for the next couple of years.

Journalism had gone from being an occasional thing for me to a regular thing. Unfortunately, NLNS was a small nonprofit serving the left-wing campus press, the remnant of the ’60s underground press, and some larger community media outlets. Most of which were too broke to pay much for the news packets my service was producing for them. Thus, I wasn’t able to make ends meet doing it for very long. And by 1991, I was temping again on the side.

No more manual labor for me, though. That was over, given my damaged vertebrae. This time any temp assignments I took had to make use of my writing, editing, and research skills—which I had developed over the previous few years, despite not having a college degree… and not getting one until 2006.

After a number of short assignments, I found a long-term editing gig via a jobs bulletin board at MIT that anyone in the know could just walk up to and use. Faxon Research Services, a now-defunct database company, contracted me through a temp agency. It was March 1992.

Over the months, I did well enough at the assignment that I was granted my own office and more responsibilities. I also helped the other NLNS staffer of the time to get a similar gig at Faxon. He, too, started getting more responsibility at the office. Soon, I was being groomed for a full-time job by one vice president. He was being groomed by another vice president. The two vice presidents were at odds with each other. My vice president lost the inter-departmental war. And my temp contract was ended in December 1992. Just like that.

Because that’s how temp jobs, and indeed most forms of contingent employment function. Employers want the freedom to use workers’ labor when they need it and to get rid of them the moment they don’t. While paying the lowest wages possible. Saving labor costs and increasing profits in the process.

Faxon assumed that, like every other temp, I was just going to take the injustice of losing my shot at a long-term full-time job lying down.

But not that time. And I would never accept injustice at any gig ever again. I had learned one key lesson from getting badly injured from the Manpower temp job at Belden Electronics three years previous: If I was treated unfairly in the workplace, I was going to fight. And keep fighting until I won some kind of redress.

So, I did something that temps aren’t supposed to do: I applied for unemployment. Because temp agencies and the employers that contract them use such arrangements in part to play the same “neither company is your employer” game that Manpower and Belden played when I got a spinal injury on Belden property.

However, I realized that I had been at this temp gig full-time for nine months and figured I had a chance of convincing the Mass unemployment department of the period that I was a Faxon employee in fact even if I was officially a temp at an agency that played so small a role in the gig in question that I can’t even remember its name.

My initial unemployment filing was rejected. And I appealed it. And testified to an unemployment department official. And won my unemployment. A small victory, true. But an important one for me, and possibly for other temps in similar situations in the years after me. Faxon didn’t fight the ruling. I got my money.

Fortunately, I didn’t need the unemployment payments for long. Back in February 1992, writing as I did not just for NLNS, but also for other publications, I had a chance to join a labor union in my trade. Not the traditional union I had dreamt of helping organize at Belden Electronics prior to—and certainly after—my injury. It was called the National Writers Union/United Auto Workers Local 1981. A small but trailblazing formation experimenting with organizing any of several types of contingent writers—with a constituency of freelance journalists, book authors, and technical writers.

I immediately got active in the Boston “unit” of the local. Was elected as a delegate to the national convention in the summer of 1992. Was the youngest candidate for a open vice president’s seat. Lost, but not too badly. And won enough notoriety in the Boston branch that they hired me as their half-time director in December.

My fight for justice for myself and millions of other people in temp, part-time, day labor, contract, independent contractor, migrant, and many other kinds of bad unstable contingent jobs besides took off from there. In 1993, I joined the New Directions Movement democracy caucus within the rapidly shrinking but still super-bureaucratic and timid United Auto Workers union, and learned a great deal about how all those purposely precarious employment arrangements were being used by employers to crush labor.

In 1994, I started the small national publication As We Are: The Magazine for Working Young People. In 1995, I wrote an article in its third number about the attempt by the radical union Industrial Workers of the World to start a Temp Workers Union, and began actively looking for a way to start a general labor organization for contingent workers. In 1996—just after I published the fourth As We Are, folded the magazine for lack of funds, and took a long-term temp assignment with 3M’s advertising division as a front desk person—I helped launch the Organizing Committee for a Massachusetts Employees Association (OCMEA) with Citizens for Participation in Political Action. A group that straddled the line between the left wing of the Democratic Party and socialists just to their left in the Commonwealth. In January 1997, I quit the 3M assignment a few days before being serendipitously hired by Tim Costello of Northeast Action as the half-time assistant organizer of his Project on Contingent Work there. We rolled the OCMEA effort into our new project and also helped start a nationwide network of similar contingent worker organizing projects called the National Alliance for Fair Employment later that year.

In June 1998, I left the National Writers Union gig—having helped build the Boston branch’s membership from just over 200 members to over 700 members in my six-year tenure—and took one final long-term half-time temp editor assignment through Editorial Services of New England at Lycos, a competitor of Yahoo and other early commercial search engines on the World Wide Web. I organized a shadow union of over 25 fellow temp editors— which won pay parity for men and women on the assignment—before leaving to help Costello break away from Northeast Action and begin raising money to form our own independent contingent workers’ organization in September 1998.

Finally, in January 1999, we had the funding to found the Campaign on Contingent Work (CCW), the extremely innovative labor organizing network that did much to help workers in bad jobs in Massachusetts over the six years of its existence.

That year we also expanded the national contingent organizing group into Canada to form the North American Alliance for Fair Employment (NAFFE)—which was also based in Boston. Ultimately, Costello was the coordinator of that group and I was coordinator of CCW. And in 2003, during conversations with the CEO of Manpower about a temp industry code of conduct that NAFFE had drafted, Costello started telling him the story of my injury on a Manpower assignment. The CEO cut him off a few sentences in and said, “Forklift?” And Costello said, “Yes.” And the CEO apparently said that years after my injury, so many workers had been hurt driving forklifts in Manpower temp jobs that there had been some kind of settlement with them and the company had instituted reforms. I never bothered to verify the tale. But I don’t doubt its veracity.

Because employers can only push workers so far before we start to push back. And I’ve written this series for one reason: to encourage readers in bad jobs in the (now rather old) “new economy” to push back. To fight where you stand. To stop accepting unstable gigs with no benefits for low pay. To start demanding a better deal. Together with your fellow workers. And to keep demanding it. Until we live in a world where no one will ever have to work a bad job. Or get permanently injured the way I did.

Check out part one of “From Injury to Action” here and part two here.

Apparent Horizon—winner of the Association of Alternative Newsmedia’s 2018 Best Political Column award—is syndicated by the Boston Institute for Nonprofit Journalism. Jason Pramas is BINJ’s network director, and executive editor and associate publisher of DigBoston. Copyright 2018 Jason Pramas. Licensed for use by the Boston Institute for Nonprofit Journalism and media outlets in its network.

FROM INJURY TO ACTION: A LABOR DAY REMEMBRANCE (PART II)

October 3, 2018

BY JASON PRAMAS @JASONPRAMAS

In part one (DigBoston, Vol. 20, Iss. 36, p. 6), I related how working a temp factory job at Belden Electronics on assignment for Manpower for several weeks in early 1989 in Vermont led to my sustaining a sudden and permanent spinal injury while walking to my car just after my last shift. At the conclusion of that narrative, I was standing in agony in an empty parking lot outside an empty factory in the middle of the woods in the middle of the night in a snowstorm. My left arm was essentially paralyzed. I was completely alone.

I staggered the remaining distance to my car. Struggled to get the keys out of my left pants pocket with my good right arm. Unlocked the door. Opened it. Tumbled into the driver’s seat. Pulled the shoulder belt over my numb left arm. Waves of pain coursed through my body. Got the car started.

“Can’t pass out,” I told myself, “Don’t have much gas left, and once it’s gone, the heat goes. I can get hypothermia before anyone notices me in here. Could die.”

It was hard to hold my head upright enough to drive, but I managed it. Harder still was getting the car in gear and then driving stick with only my right arm. In a snowstorm. In the middle of the night. Drifting each time my hand was on the stick. Nearly braking into a spin each time I approached top speed in a gear while my hand was on the steering wheel. Nearly stalling whenever I downshifted. And, yeah, that busted second gear I mentioned in part one? That was a real problem. It was tricky enough jumping from first to third gear and back when I wasn’t injured. Doing it while badly hurt and trying to drive one-handed on dangerously icy roads for the roughly half hour I figured it would take me to get from Essex Junction to the emergency room at the big Medical Center Hospital of Vermont in Burlington? That was just asking to get put out of my misery the hard way.

But that was what I set out to do. Why? Not sure. I was fairly lucid, but I wasn’t exactly thinking clearly. Still, not much was open after 9 pm in the rural suburbs of Burlington in the late 1980s. Especially with the snow falling harder with each passing minute. My recollection is that, given the route I was taking, the first gas station that was likely to be open was close enough to the hospital that I might as well drive the full distance myself and skip an ambulance ride I couldn’t afford. And I hadn’t lived in the area long enough to know if there were any emergency rooms closer to my location.

The other problem I faced was the the hypnotizing effect of my headlights reflecting off snowflakes as I drove down unlit back roads. To avoid accidentally getting confused, losing the road, and slamming into something solid, I stayed mostly in first gear. So it took longer to get to my destination. Maybe 45 minutes. Fortunately, I encountered little traffic on the way. And made it to the emergency room.

There I got treated the way people without insurance get treated all the time in America. Like dirt. I sat in the waiting room for over an hour. The bored resident that eventually saw me gave me a cursory examination and sent me for an X-ray. More accurate MRIs weren’t yet common and certainly wouldn’t have been given to patients without coverage at that time. I spent the next couple of hours in an emergency room bay. There was a heroin epidemic in Vermont in that period, so I was offered no pain killers in case I was just another junkie “drug seeker” trying to pull a fast one on the staff for a quick opiate fix.

Finally, the resident returned, and told me that I had dislocated two vertebrae. He gave me a few Tylenol, told me to put heat on my injury, rest for a few days, and see a general practitioner if my arm function didn’t fully return. I was not admitted for more tests or observation. I was not offered stronger pain meds. I was incredulous, but could do nothing. Naturally, I didn’t pay the medical bill when it arrived.

I shuffled back to my car and drove the mile to my apartment. Down the quite steep and icy hill from the University of Vermont campus where the hospital was located to the Old North End. Still one-handed, although I was getting some feeling back in my left arm by that time. At least the snow had let up.

It was 5 am. I got the front door open. Closed it. Got a glass of water. Took some Tylenol. Went to my room. Shut that door. Collapsed onto my futon on the floor of my dingy place that was cheap even by the standards of Burlington in that era. Slept fitfully.

Woke a few hours later to the first day of my new life as a bona fide member of the walking wounded.

It should go without saying that in the days to come both Belden Electronics and the temp service they used to hire me, Manpower, refused to accept responsibility for my injury. Neither company even informed me of my workers’ compensation rights. And I was too young and inexperienced to know much about labor law on my own. So, I proceeded with no money for medical treatment.

Surrounded, as I was, by wide-eyed hippies of the type that Vermont is justifiably infamous for producing, I was strongly encouraged to drop the idea of seeking help from “Western medicine” and seek assistance from one or more of the profusion of “holistic healers” that littered the hills and valleys of my temporarily adopted state like so many locusts. I went with the modality that most closely mimicked actual scientific medicine: chiropractic. Because, you know, its practitioners like to wear white coats and pretend they’re doctors. Regardless of whether they’re in the small minority of their colleagues that restrict their practice to scientifically proven treatments, or the majority that does not.

Unaware that a) with rest and some physical therapy my injury would probably heal to a tolerable baseline on its own within a few weeks, and b) that the neck twisting employed by less scrupulous chiropractors when “treating” injuries like mine carried a very real risk of inducing a life-ending stroke, I gamely allowed to a succession of chiropractors to twist my neck really fast until its vertebrae cracked. In addition to a fairly random grab bag of similar “treatments.” First once a week and later once a month for the next six years. At $30 a visit to start—up to about $60 a visit by the time I realized my trust in chiropractors was misplaced and stopped letting such charlatans violate my person—the price was significantly cheaper than any medical care I thought I could get without insurance.

So, despite feeling worse after every session than I felt when I walked in, I kept it up for far too long. Which was the goal of too many chiropractors. Whatever brings you in their door, they aim to keep you coming back regularly for the rest of your life. Assuming they don’t inadvertently end it. Or merely hurt you badly. As happened when my last chiropractor decided to try electro-muscular stimulation near my head and my vision exploded into whiteness, which faded for an unknown amount of time until I awoke with my face on the quack’s chest. Weak. Somewhat confused. And very angry. I walked out and never came back.

But five years later—over 11 years after the initial injury—I discovered that more damage had been done to my spine. No doubt in part from such ungentle and unschooled ministrations. A story for another day.

Check out part one of “From Injury to Action” here and part three here… and for more information on why chiropractic is best avoided, check out the Science-Based Medicine blog (sciencebasedmedicine.org/category/chiropractic/) and the older Chirobase (chirobase.org).

Apparent Horizon—winner of the Association of Alternative Newsmedia’s 2018 Best Political Column award—is syndicated by the Boston Institute for Nonprofit Journalism. Jason Pramas is BINJ’s network director, and executive editor and associate publisher of DigBoston. Copyright 2018 Jason Pramas. Licensed for use by the Boston Institute for Nonprofit Journalism and media outlets in its network.

SEA LEVEL RISE IS JUST ONE OF BOSTON’S WORRIES

As Earth approaches several catastrophic global warming “tipping points”

January 24, 2018

BY JASON PRAMAS @JASONPRAMAS

Before writing more columns examining Boston city government’s emerging plans to cope with the effects of global warming, I think a quick review of what area residents are likely to face in the coming decades is in order. Because it’s important to disabuse people of the idea that we’re dealing with “just” a handful of significant problems over time—a rise in air temperature, an increase of extreme weather events, and a rise in sea level—that those problems are isolated to just Boston or the United States, that they are going to continue until the end of the century and then stop, and that there are some simple things we can do to prevent those problems from becoming unmanageable.

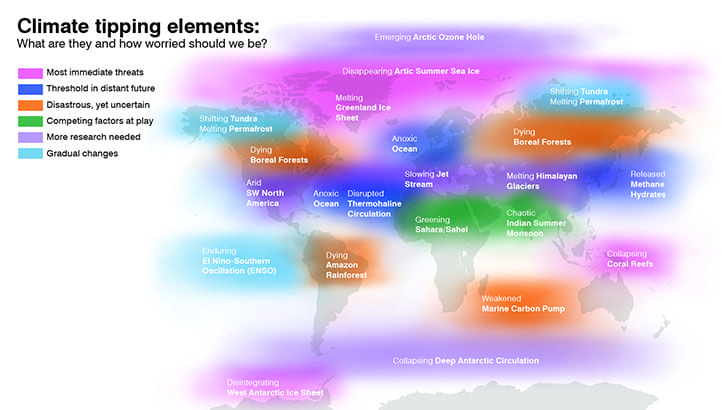

The reality is far more frightening. According to Mother Jones, “In 2004, John Schellnhuber, distinguished science adviser at the Tyndall Centre for Climate Change Research in the United Kingdom, identified 12 global-warming tipping points, any one of which, if triggered, will likely initiate sudden, catastrophic changes across the planet.”

There’s been much research and debate since that time about which systems can be considered tipping points and which ones need more research before we can be sure, but the Environmental Defense Fund has a page on its website with an overview of the latest science. It’s called “Everything you need to know about climate tipping points” and you should read it in full. But here’s a quick summary of the tipping points that the Earth is passing or on its way to passing. Largely due to humans continuing to burn CO2-producing oil, gas, and coal decades after it was known to be suicidal to do so.

1) Disappearance of Arctic Summer Sea Ice

The poles are warming faster than the rest of the planet. In the Arctic, sea ice has been melting much more quickly than it used to for much more of every year as the average global temperatures rise year after year. Scientists are now predicting ice-free Arctic summers by mid-century. The less of the year that ice covers the Arctic, the less sunlight is reflected back to space. Sunlight that is not reflected warms the Arctic Ocean, leading to other problems and more global warming overall.

2) Melting of the Greenland Ice Sheet

Of particular concern to Bostonians because of our relative proximity to Greenland, the melting of its ice cap may continue for the next few hundred years until there is none left. Unlike melting sea ice that doesn’t add water to the world’s oceans, melting ice from land does. This will ultimately result in global sea level rise of up to 20 feet, and the process is underway.

3) Disintegration of the West Antarctic Ice Sheet

This tipping point may already have been passed—with the West Antarctic ice sheet already starting to collapse. Like the Greenland ice sheet, it too is expected to take hundreds of years to finish melting, but when it does it could raise the global sea level up to 16 feet.

4) Collapse of Coral Reefs

With oceans already warming and becoming more acidic, the algae eaten by the coral that make up the world’s often huge and spectacular reefs is being jettisoned, resulting in coral bleaching. This process weakens the coral and hastens its death. Which is accelerating the destruction of marine spawning and feeding grounds globally with dire consequences for many nations whose economies rely on them—and for biodiversity. Scientists now predict that the remaining coral reefs will collapse before there is rise in the global temperature of 2 degrees from the old normal average. Most climate models show the world reaching that threshold before the end of this century.

Beyond these, there are several other expected tipping points being studied: the disruption of ocean circulation patterns from the massive influx of fresh water from melting ice (especially in the North Atlantic, which would play havoc with Boston’s climate), the release of marine methane hydrates (which would accelerate the global warming already being caused by the CO2 emissions considered the main cause of climate change), ocean anoxia (a process creating growing oxygen-deprived “dead zones” in our oceans that can no longer support most life, aka “bye bye seafood”), the dieback of the Amazon rainforest (caused by human activity like cutting down huge numbers of trees with devastating consequences for biodiversity coupled with the loss of a major CO2 sink), the dieback of the boreal forests (still being studied, but means the death of more vast forests in and around our latitude of the planet), the weakening of the marine carbon pump (the Earth’s oceans have been absorbing much of the excess carbon in the atmosphere, but through this process will become less effective at it), the greening of the Sahara (some positive effects would come from this, but many basic ocean life forms rely on nutrients from the desert sand blowing into the ocean and will be negatively affected by losing it), and the increasingly chaotic Indian summer monsoons (could result in extensive drought in one of the Earth’s most populous regions).

Other processes underway may also be potential tipping points, including the collapse of deep Antarctic ocean circulation, the appearance of an Arctic ozone hole (joining the existing Antarctic ozone hole in causing rising UV levels in the Arctic with various negative effects), the aridification of the US Southwest (as moisture moves to the upper Great Plains), the slowdown of the jet stream (which could leave more weather systems stuck in place for weeks at a time, including extreme systems like our recent polar vortex-induced cold wave, among other negative effects), the melting of the Himalayan glaciers (which help provide fresh water for much of South Asia’s population), a more permanent El Niño state (which could result in more drought in Southeast Asia and elsewhere), permafrost melting (which results in more CO2 and methane being released, accelerating global warming further), and tundra transition to boreal forest (with uncertain effects).

Adding the above to the general effects of global warming that we’re already experiencing—areas that got lots of rain getting less and areas that got little rain getting more rain storms for more of the year, hotter temperatures overall leading to an array of bad effects like tropical diseases moving north, and the “sixth extinction” of large numbers of species of animals and plants—and keeping in mind that this is happening everywhere around the planet, readers should understand that we’re not facing a localized crisis.

And remember, all the processes mentioned above are interlinked in complex ways that are absolutely not fully understood by our current science.

So Boston is not just going to “trial balloon and town hall meeting” its way out of this array of existential crises. Surviving even one of the major problems caused by global warming—like the flooding from rising sea levels I wrote about last week—is going to be very difficult… and very expensive. And who’s going to pay for it? Well, going forward, in addition to pointing out that we’ll have to devote an ever-increasing percentage of public budgets to these problems, expect me to call for the corporations that started and continue to profit from global warming—the oil, gas, and coal companies—to pay for cleaning up the mess they created. To the degree possible. Which might not be sufficient to the monumental tasks at hand.

Still, it will be critical for Boston to join municipalities like New York City in suing the carbon multinationals Exxon, Chevron, BP, Shell, ConocoPhillips, and others for redress. While divesting the city from all investments in those companies’ stocks. And suing, and ultimately deposing, governments like the Trump administration that are aiding and abetting these corporations’ destruction of the planet.

Failing that, Boston and all of human civilization is literally sunk… burned… and perhaps ultimately suffocated. Dying not with the bang of nuclear war—itself a fate we also need to organize immediately to avoid given the federal government’s return to atomic sabre rattling—but with an extended agonizing whimper.

It’s up to all of us to stop that from happening.

Apparent Horizon is syndicated by the Boston Institute for Nonprofit Journalism. Jason Pramas is BINJ’s network director, and executive editor and associate publisher of DigBoston. Copyright 2018 Jason Pramas. Licensed for use by the Boston Institute for Nonprofit Journalism and media outlets in its network.

THE SEAPORT FLOOD IS JUST THE BEGINNING

Unless Boston builds proper defenses against global warming-driven sea level rise

January 17, 2018

BY JASON PRAMAS @JASONPRAMAS

So, Boston’s Seaport District flooded early this month during a bad snowstorm in the midst of several days of arctic temperatures. And nobody could be less surprised than me. Because I’ve spent a lot of the last quarter century closely following developments in the science of climate change. And the “bomb cyclone” that caused the flooding, and the polar vortex that caused that, are both likely to have been caused by global warming. Yale University Climate Connections just produced a great video that features several luminary climate scientists explaining why at yaleclimateconnections.org. Definitely check it out.

No question, though, that it’s good to live in a region where local government at least recognizes that global warming is a scientific reality. The city of Boston is certainly ahead of most municipalities in the US in terms of laying plans to reduce greenhouse gas emissions enough to become “carbon neutral” and to deal with some of the anticipated effects of climate change. Particularly, flooding from inexorably rising sea levels and increasingly powerful and frequent storms. Which the more reactionary Boston TV newsreaders still insist on calling “wild weather.” But its plans are largely just that… plans. And they are still incomplete and, frankly, woefully inadequate to deal with the magnitude of the crisis facing us all.

Boston city government has initiated an array of climate change initiatives, including Greenovate Boston, a section of the Imagine Boston 2030 process, and—most germane to this discussion—Climate Ready Boston. They are all producing very nice reports grappling with some of the challenges to humanity presented by global warming in the decades to come. But the reports are written by planners and experts who are clearly pulling their punches for reasons that remain somewhat opaque. And in doing so, any good that might come out of the reports and the policy actions that will result from them is essentially undone.

A look at metro planning on global warming-induced flooding is a good way to illuminate the problem in question. The Climate Ready Boston program released a 340-page report in December 2016 that was meant to be a comprehensive assessment of the threats presented to the city by global warming—with plans for possible correctives. It does mention the idea of building giant dikes, storm barriers, and retractable gates (which they call a “harbor-wide flood protection system”) across Boston Harbor as the method with the most potential to save much of the city from major flooding. Which makes sense since Mayor Marty Walsh signed a 2015 agreement with Dutch officials to work together to manage rising sea levels, according to Boston Magazine. And the Dutch are recognized world experts on giant storm barriers and hydroengineering in general, lo, these last few hundred years.

But there’s no firm commitment for harbor-wide defenses in the report. Yet it should be obvious that they are absolutely necessary if Boston is going to continue as a living city for even a few more decades. At least Amos Hostetter of the Barr Foundation—who is a major player in Boston’s climate efforts—put up $360,000 for the UMass Boston Center for the Environment to study their feasibility last year, according to the Boston Globe.

More concerning than its waffling on building big dikes, the big Climate Ready Boston report chooses to focus on the possibility of sea level rise of no more than 3 feet by 2070—although it allows that a rise of 7.4 feet is possible by 2100:

The highest sea level rise considered in this report, 36 inches, is highly probable toward the end of the century if emissions remain at the current level or even if there is a moderate reduction in emissions. … If emissions remain at current levels, there is an approximately 15 percent chance that sea levels will rise at least 7.4 feet by the end of century, a scenario far more dire than those considered here.

Similar caution is on display with an October 2017 Climate Ready Boston report called “Coastal Resilience Solutions for East Boston and Charlestown”—focusing on tactics to protect two Boston neighborhoods on Boston Harbor at high risk for flooding caused by global warming. Once again, the authors’ assumption is that global warming-related sea level rise in Boston will be no more than 3 feet higher than year 2000 figures by 2070. Even though such estimates—which we have already seen are conservative by Climate Ready Boston’s own admission—also indicate that we could face 7-plus feet of sea level rise or more by 2100. And even higher rises going forward from there. Because sea level rise is slated to continue for generations to come.

What’s weird about such methodological conservatism is that a 2016 paper in the prestigious science journal Nature co-authored by a Bay State geoscientist says the lower figures that all the city’s climate reports are using already look to be wildly optimistic.

According to the Boston Globe:

“Boston is a bull’s-eye for more sea level damage,” said Rob DeConto, a climate scientist at UMass Amherst who helped develop the new Antarctica research and who co-wrote the new Boston report. “We have a lot to fear from Antarctica.” … If high levels of greenhouse gases continue to be released into the atmosphere, the seas around Boston could rise as much as 10.5 feet by 2100 and 37 feet by 2200, according to the report.

What’s even weirder is that the same UMass scientist, Rob DeConto, co-authored a detailed June 2016 report for Climate Ready Boston called “Climate Change and Sea Level Rise Projections for Boston: The Boston Research Advisory Group Report” with 16 other climate scientists that look at an array of possible outcomes for the city—and include a discussion of the higher sea level rise figures mentioned in the Nature paper. The report concludes with an admission that current science doesn’t allow for accurate predictions of climate change in the second half of the century. All the more reason, one would think, that models predicting higher than anticipated sea level rise should not seemingly be dismissed out of hand in other Climate Ready Boston reports.

The Globe also reported that a study by the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) says Boston can expect a sea level rise of 8.2 feet by 2100. Both 8.2 foot and 10.5 foot estimates are higher than the 7.4 foot estimate that Climate Ready Boston says is possible by 2100, and well above the 3 feet that it is actually planning for by 2070.

The same team that produced the larger Climate Ready Boston report authored the East Boston and Charlestown report; so they are doubtless quite well-aware of all this. Which is evident in this sentence about the (insufficient) extensibility of their proposed neighborhood-based flood defenses: “If sea levels rise by more than 36 inches, these measures could be elevated at least two feet higher by adding fill, integrating structural furniture that adds height and social capacity, or installing deployable flood walls. With this built-in adaptability, their effectiveness could be extended by an additional 20 years or more.”

The point here is not that the Boston city government is doing nothing about global warming-induced flooding. It’s that the city is potentially proposing to do too little, too late (given that most of the flood defenses it’s proposing will remain in the study phase for years, and many will protect specific neighborhoods but not the whole city when finally built), for reasons that aren’t entirely clear. Though it’s probable that those reasons are more political and economic than scientific. Avoiding scaring-off the real estate developers and major corporations that provide much of the current city tax base, for example. The kind of thing that will make life difficult for politicians who then make life difficult for staffers and consultants working on global warming response plans.

Regardless, if experts like the Dutch are basically saying, Boston really needs to build the biggest possible harbor-wide flood protection system to have any hope of surviving at least a few more decades, then we can’t afford to do one of the more half-assed versions of the big cross-harbor storm barrier plan mentioned in the original Climate Ready Boston report—or, worse still, fail to build major harbor-wide defenses at all. If major studies by climate experts are saying that 3 feet of sea level rise by 2070 and 7.4 feet by 2100 are overly optimistic figures, then we need to plan for at least the highest reasonable estimates: currently, the NOAA’s 8.5 feet or, better yet, the Nature paper’s 10.5 feet for the end of the century. It’s true that we could get smart or lucky and avoid those numbers by 2100. But what about 2110? Or 2150? Or 2200? Sea level rise is not just going to stop in 2070 or 2100.

Are city planners and researchers willing to gamble with the city’s fate to avoid sticky political and economic fights? Let’s hope not. For all our sakes. Or the recent Seaport District flood—and numerous other similar recent floods—will be just the start of a fairly short, ugly slide into a watery grave for the Hub.

Apparent Horizon is syndicated by the Boston Institute for Nonprofit Journalism. Jason Pramas is BINJ’s network director, and executive editor and associate publisher of DigBoston. Copyright 2018 Jason Pramas. Licensed for use by the Boston Institute for Nonprofit Journalism and media outlets in its network.

ON MAKERSPACES AND SOCIAL RESPONSIBILITY

Making can be cool, but conscious making is cooler

December 19, 2017

BY JASON PRAMAS @JASONPRAMAS

For many of us living in and around Boston in recent years, it has become common to see lots of communications from makerspaces around holiday time. Which is totally understandable. Such creative centers produce neat things year-round, so it’s only natural that their members would turn to producing gifts like busy elves (and holding workshops about how to produce gifts like… um… smart busy elves) as fall turns to winter.

However, if you’re someone who thinks critically about social institutions and their interaction with technology, then you might join me in feeling some concern about the trajectory of these spaces. Which boils down to this: Do makers and the makerspaces they found think about why they make, and for whom they make? Obviously, it varies from maker to maker and space to space, but my observation has been that the maker movement could do much better on that front. So I thought I would run through some of my apprehensions on that theme and make some suggestions for reform. In the spirit of holiday giving and all that.

There’s no question that makerspaces have been a boon to society in many different ways. Described by the Somerville nonprofit makerspace Artisan’s Asylum as “community centers with tools,” these logical outgrowths of the hacker and DIY cultures—and the older crafter culture, amateur radio culture, and cultures around magazines like Popular Electronics and Popular Mechanics—have grown to become a significant social force in the last decade. Particularly in places like the Boston area that have lots of colleges producing lots of engineers, scientists, and artists.

But it’s important to remember that—as with science, technology, and art in general—there is a problem with pushing “making” in the abstract without thinking about its social and political consequences. Because tools and techniques may be inherently neutral, but people and the institutions we create are not.

Including makerspaces. So it’s worth being aware that, according to PandoDaily, in early 2012 O’Reilly Media’s MAKE division —publisher of Make magazine, perhaps the best known popularizer of the maker movement—announced that it had won a grant from the Pentagon’s Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA) to participate in the agency’s Manufacturing Experimentation and Outreach (or MENTOR) program. The money was to be used to start 1,000 makerspaces in high schools around the country.

Now DARPA may be most famous as the super clever agency that brought us the Internet. But it worked on that project in part—protestations from its fans and allies taken as given—to help solve the insoluble problem of how to keep America’s military, research, and control centers in communication with each other after an all-out nuclear war. And somehow help our government survive the unsurvivable.

It is also the super clever agency that has brought us an array of very nasty war machines in the last six decades. Notably, according to Air & Space magazine, the Predator drones that have killed hundreds of innocent people around the world—including many children—in recent years at the behest of presidents from Bush to Obama to Trump. Because they’re just not as accurate as our military and political leaders would have us believe. And because those leaders don’t really care about what they call “collateral damage” when they’re prosecuting what human rights groups like the American Civil Liberties Union and the Center for Constitutional Rights claim are extralegal assassination campaigns.

As it turned out, the DARPA MENTOR high school program never really got off the ground because it lost its budget in President Obama’s big “Sequestration” budget cut of March 2013. And it’s certainly worth mentioning that the program sparked protests from within the maker community.

But DARPA continues to participate in a variety of science and technology events aimed at high school kids—notably the young robotics crowd that overlaps with makerspaces.

And DARPA is also aiming events squarely at makerspaces… and some makerspaces are definitely participating. For example, according to the DARPA website, this November the agency held the DARPA Bay Area Software Defined Radio (SDR) Hackfest at NASA Ames Conference Center in Moffett Field, California. The relevant webpage explains that “Teams from across the country will come together to explore the cyber-physical interplay of SDR and unmanned aerial vehicles, or UAVs, during the Hackfest.”

“Unmanned aerial vehicles” is another term for drones. Two of the eight teams invited to participate along with teams from military contractors like Raytheon were the Fat Cat Flyers from Fat Cat Fab Lab, a volunteer-run makerspace in New York City, and Team Fly-by-SDR from Hacker DoJo, a nonprofit community of hackers and startups in Silicon Valley… which is also a makerspace.

Whatever you in the viewing audience think about the Pentagon in particular and the American military in general, we can all agree that there are moral, ethical, social, and political questions that must be asked in a democratic society about the intersection of maker culture and makerspaces with those institutions.

For that reason, I think it’s critical that makerspaces raise and address such questions on an ongoing basis. That they maintain a scrupulous policy of transparency regarding who they work with and why. And that they hold classes and public forums on the moral, ethical, social and political dimensions of why makers make and for whom they make. Something you really don’t see much of at makerspaces at present. But should.

Anyhow, I’m keen to engage with the maker community on this topic and flesh these ideas out more. Folks interested in discussing the issues I’m raising at more length can drop me a line at execeditor@digboston.com.

A shorter version of this column was originally written for the Beyond Boston regional news digest show—co-produced by the Boston Institute for Nonprofit Journalism and several area public access television stations.

Apparent Horizon is syndicated by the Boston Institute for Nonprofit Journalism. Jason Pramas is BINJ’s network director, and executive editor and associate publisher of DigBoston. Copyright 2017 Jason Pramas. Licensed for use by the Boston Institute for Nonprofit Journalism and media outlets in its network.