Buy ads in our pages or tell your bosses to buy them today!

Jason Pramas

A Home in the Digital World

Budget

POPULAR NOT POPULIST: GOV BAKER CONTINUES TO POLL WELL WITH PEOPLE HE’S SCREWING

July 31, 2018

BY JASON PRAMAS @JASONPRAMAS

There is no area of Massachusetts politics where it is more baffling to contemplate Gov. Charlie Baker’s ongoing popularity in the polls than the annual state budget debate. One can only draw two conclusions from such musing: either people don’t get the budget information they need from Bay State press, or a majority of Commonwealth residents simply enjoy watching poor people get kicked to the curb. While corporations are encouraged to line their pockets with public funds in ways that hurt everyone but the wealthy.

At no time of year is the contradiction of Baker’s popularity thrown into bold relief more than late July when he issues his line item vetoes and other modifications to the legislature’s final budget.

And this year that contradiction is sharper than ever. Because the most visible victims of the governor’s last budget action look to be people on welfare—many of whom are single mothers with children.

So last week, Baker refused to agree to a budget policy section that would remove the “family cap” that stops families on welfare from being able to receive extra benefits for children born while they were on welfare. Instead he sent an amended version of the family cap section of the state budget back to the legislature.

As reported by MassLive, “That amendment would lift the family cap but also change welfare eligibility laws so that an adult’s Supplemental Security Income is counted when determining if a family is eligible for welfare. SSI is a federal payment given to severely disabled adults.” … “According to state figures as of last year, 5,200 children with a severely disabled parent would lose their welfare benefits entirely under the change, and 2,100 children would lose part of their benefit.”

By contrast, MassLive continues, “Lifting the family cap would make approximately 8,700 additional children eligible for welfare assistance.”

If the family cap policy section of the budget had simply been vetoed, it could have been overridden by a two-thirds vote of the legislature like any other veto. But since its language was amended and sent back to the legislature for action, they have to vote on it like a new bill. After which, Baker has 10 days to act on it. And since he sent it back to the legislature at the end of its current session, the end of the 10 days after any new bill passes comes after the session is over. So Baker can simply veto it, and supporters will have to wait until next session to go through the entire legislative process again.

Advocates from organizations like Mass Law Reform Institute and Greater Boston Legal Services are crying foul, given the heartlessness of the measure and the fact that it has taken years to get the family cap reform through the legislature.

As of this writing, the House has reinstated the original family cap language, and the Senate is expected to do the same. But Baker will almost certainly veto it within 10 days of passage as planned. After the legislative session has ended.

Which is a total drag, and exemplary of a backwards view of welfare as an “incentive” to “encourage” poor people to work. Language that Baker has used when explaining his position on the family cap debate—a standard conservative view, unfortunately shared by Republicans and many Democrats alike, that poor people are poor because of individual failings like “laziness,” not for any structural reasons beyond their immediate control.

But here’s another way to view welfare: People are poor because just as capitalism provides billions of dollars to a vanishingly small number of big winners like Jeff Bezos and the Koch brothers, it creates millions of losers who have to struggle endlessly to make ends meet. Meaning inequality is baked into our economic system. Without strong government regulation, capitalism is incapable of even blunting the brutal impact of such inherent flaws, let alone somehow fixing those flaws.

Part of that inequality comes in the form of job provision. Since the drive for people at the commanding heights of the capitalist system is always to maximize profits, their concomitant drive is to do so by slashing labor costs whenever possible. One way they have done this since the 1970s is by changing labor from a fixed cost—as it tended to be under postwar American social democracy when over 30 percent of the workforce was protected by government-backed union contracts and there was a reasonable social safety net (including welfare)—to a variable cost.

The result? As was last the case at the turn of the 20th century while a militant labor movement spent decades fighting the “robber baron” billionaires of that era for redress, bosses can hire workers when needed at the worst possible rates and push them out when they don’t need them. Often without even having to officially fire workers—which would allow them to collect unemployment for a few months. And the largely ununionized workforce has almost no say about the conditions of its employment, or job policies in general, outside of insufficient minimum wage laws, easily avoided health and safety laws, and a few increasingly weak civil rights laws that might get a handful of people reinstated on the same bad terms on the rare occasions when open discriminatory practices by employers can be proven.

So by converting stable decent-paying union jobs to unstable contingent jobs—like temp, part-time, contract, day labor, and independent contractor jobs—over the last 40 years, capitalism and the capitalists who run it have ensured the creation of a growing impoverished underclass. This vast group of poor people acts as a reserve army of labor that, together with vicious union-busting that is on the verge of killing the American labor movement, accelerates the downward pressure on wages. And ensures that the only jobs that most poor people can get are bad contingent jobs.

When poor people can’t put together enough of these precarious non-jobs to make ends meet, they turn to welfare. But the old “outdoor relief” programs that provided poor men with jobs, money, food, and other necessities in many parts of the country were eliminated long ago (as were New Deal-era public jobs programs), and the remaining welfare system that largely benefitted poor women and children was hamstrung by the Democratic Clinton administration in 1996. Not coincidentally, its prescriptions were first tested here in Massachusetts in 1995 by our completely Democrat-dominated legislature—presided over by a Republican governor, Bill Weld. A so-called “libertarian” cut from much the same cloth as Charlie Baker.

According to a 2008 report (“Following Through on Welfare Reform”) by the Mass Budget and Policy Center, the one-two state-federal punch to poor women and children in the Commonwealth predictably ended up significantly cutting already meager welfare payments by imposing time limits on assistance and by mandating the most cruelly ironic possible change, “work requirements.”

Why cruelly ironic? Because the work requirements forced people who were poor because the only jobs available to them were bad contingent jobs to prove they were “working” before getting the reduced welfare benefits still on offer.

The new system was in many cases literally run by the very temp agencies that played a key role in making people poor to begin with. The “jobs” forced on people to qualify for much-denuded benefits were often not jobs at all. Welfare applicants were just “employed” by such temp agencies—now recast as privatized social service agencies—and forced to wait for “assignments” that were low-paying and sporadic. But unless they “worked” a certain amount under this system, no benefits. It was a hardline right-winger’s wet dream made flesh. The same capitalist system that made them poor now kept them poor. And state and federal government were no longer in the “business” of helping offset the worst depredations of capitalist inequality in what we still like to call a democracy.

So this is what popular Gov. Charlie Baker is up to when he plays games with reforms like the family cap. He’s screwing people who get a few hundred bucks a month in benefits out of an extra hundred a month for another kid born while they’re jumping through every conceivable time-wasting bureaucratic hoop and working the same shit jobs that made them poor to begin with. Meanwhile, he’s finding new and creative ways to dump more millions in public treasure on the undeserving rich with each passing year.

And you like this guy, fellow Massholes?! Just remember, in a “race to the bottom” economy presided over by capitalist hatchet men like Baker, once the poor are completely crushed, the working class is next. Followed by the middle class. Maybe think that over next time a pollster asks your opinion of the man.

Apparent Horizon—winner of the Association of Alternative Newsmedia’s 2018 Best Political Column award—is syndicated by the Boston Institute for Nonprofit Journalism. Jason Pramas is BINJ’s network director, and executive editor and associate publisher of DigBoston. Copyright 2018 Jason Pramas. Licensed for use by the Boston Institute for Nonprofit Journalism and media outlets in its network.

GRAND SCHEME

Mass legislature helps, harms workers in “deal” with labor and business lobbies

June 26, 2018

BY JASON PRAMAS @JASONPRAMAS

No sooner did the Supreme Judicial Court shoot down the “millionaires’ tax” referendum question last week than the Mass legislature rammed a so-called grand bargain bill (H 4640) through both chambers. A move aimed at shoring up tax revenue threatened by the Retailers Association of Massachusetts referendum question that is virtually certain to lower the state sales tax from 6.25 percent to 5 percent if it should go before voters in November.

The house and senate did this by rapidly completing the brokering of a deal that had been in the works between pro-labor and pro-business forces on those issues for months. Giving each side something it wanted in exchange for encouraging the Raise Up Mass coalition to take its remaining two referendum questions—paid family and medical leave, and the $15 an hour minimum wage—off the table, and the retailers association to do the same with its sales tax cut question. Both organizations have not yet made the decision to do so.

If passed, the so-called grand bargain bill will give labor watered-down versions of its paid family and medical leave and $15 an hour minimum wage ballot questions, and give business something that’s explicitly anti-labor: the end of time-and-a-half wages for people working Sundays and holidays, and their ability to legally refuse to work Sunday and holiday shifts.

While Gov. Charlie Baker still has to sign the bill, as of this writing it’s looking like he will do so. Soon.

Which is a pity because it’s not such a great deal for working people as written. True, the grand bargain does ensure that the state minimum wage will raise to $15 an hour for many workers. But it moves up to that rate from the current $11 an hour over five years, instead of the four years it would take with the referendum version. Plus it betrays tipped employees, whose wage floor will only rise from a pathetic $3.75 an hour now to a still pathetic $6.75 an hour by 2023. Keeping all the cards in the bosses’ hands in the biggest tipped sector, the restaurant industry. Although it’s worth mentioning that even the referendum version of the $15 an hour wage plan would have only raised tipped employees to $9 an hour. When what’s needed is a single minimum wage for all workers.

It also makes Massachusetts one of the first states in the nation to institute paid family and medical leave for many workers. Which is truly a noteworthy advance. Yet again, the referendum version is better for workers than the grand bargain version.

But legislators gave away another noteworthy advance from 20 years ago in the process: time-and-a-half wages for many employees who work on Sundays and holidays. Which will hurt some of the same people who the new minimum wage and paid and family medical leave will help.

Thus far, the labor-led Raise Up Massachusetts coalition has had mostly positive things to say about the deal. However, the main union representing supermarket workers—many of whom currently take Sunday and holiday shifts—is already vowing to torpedo the grand bargain. Even though their union contracts also mandate time-and-a-half pay for working Sundays and holidays. And they’ve resolved to take down legislators who backed it over their protest.

Jeff Bollen, president of United Food and Commercial Workers Local 1445, minced no words on the subject in a recent video message to his members:

“I am really pissed off at our state legislature for stabbing retail workers in the back by taking away time and a half on Sundays and holidays for all retail workers in Massachusetts.

“Remember, it was this local union in 1994 with big business and the retail association wanting to get rid of the blue laws; so they could open up their supermarkets, their big box stores, and their liquor stores and make money on Sundays that we fought hard to get a law passed to protect you, the retail worker. And we did.”

The supermarket union leader went on to explain that state lawmakers “panicked” when the millionaires’ tax was derailed and pushed through the grand bargain to avoid losing any more revenue from the referendum question to lower the sales tax. He swore the union was “going to remove those individuals that voted against you. We’re going to get them removed and replaced with pro-labor legislators who are going to fight for the rights of working people.” And defiantly concluded: “We’re going to continue to fight. We’re going to continue to try to get this whole thing repealed.”

How much support the UFCW can expect to get from the rest of the labor movement remains to be seen. But the fact is that some Bay State working families are going to suffer nearly as much pain as gain from the grand bargain.

Worse still, there’s a deeper problem with the bill. It potentially stops the retailers’ referendum drive to lower the sales tax—which they’ve definitely put on the ballot to ensure that big businesses make more profits. But it must not be forgotten that the sales tax is a regressive tax that disproportionately harms working families. And even though the state desperately needs money for many programs that help the 99 percent, it remains a bad way to raise funds compared to a progressive tax system that would force the rich to pay higher tax rates than everyone else. Like the federal government has done for over a hundred years.

Yet since the rich and their corporations continue to rule the roost in state politics, and since a state constitutional amendment would be required to allow a progressive tax system in Massachusetts, there is no way that is going to happen anytime soon. As I wrote last week, the millionaires’ tax would have at least increased the amount of progressivity in the tax system had it been allowed on the ballot (where it was projected to win handily). But business lobbies got the SJC to stop that move.

Given that, the revenue lost from a sales tax cut would really hurt in a period when many major state social programs are already being starved for funds.

Nevertheless, many working families will take a big hit from the grand bargain bill as written: They’ll see the full introduction of the $15 minimum wage delayed by an extra year, they’ll get a worse version of paid family and medical leave, they’ll lose time-and-a-half wages on Sundays and holidays, they’ll see the sales tax remain at 6.25 percent… and if they’re tipped employees, they’ll still be made to accept a lower minimum wage than the relevant ballot question would get them and still have to rely on customers to tip them decently and their bosses to refrain from skimming those tips.

So, it would behoove Raise Up Massachusetts and its constituent labor, community, and religious organizations to stay the course with the paid family and medical leave and $15 an hour minimum wage referendum questions that are still slated to appear on the November ballot. And pro-labor forces should also be ready to lobby harder for a better deal should Gov. Baker refuse to sign the grand bargain bill.

Of course, it could very well be that the bill will be signed into law before this article hits the stands, and that labor and their allies will throw in the towel on their ballot questions. And that would be a shame.

Here’s hoping for a better outcome for Massachusetts workers. Even at this late date.

Note: Raise Up Massachusetts announced that it had accepted the “grand bargain” bill shortly before this article went to press on Tuesday evening (6.26), according to the Boston Business Journal.

Apparent Horizon is syndicated by the Boston Institute for Nonprofit Journalism. Jason Pramas is BINJ’s network director, and executive editor and associate publisher of DigBoston. Copyright 2018 Jason Pramas. Licensed for use by the Boston Institute for Nonprofit Journalism and media outlets in its network.

CAPITALIST VETO

Popular “millionaires’ tax” referendum question blocked by a pro-business SJC

June 19, 2018

BY JASON PRAMAS @JASONPRAMAS

The Fair Share Amendment—better known as the “millionaires’ tax”—that would have gone before voters this November as a statewide referendum question was shot down this week by the Massachusetts Supreme Judicial Court (SJC). So the effort to increase taxes on people making $1 million-plus a year and spend the resulting funds on social needs is over. For the moment.

Organized over the last three years by Raise Up Massachusetts, a major coalition of labor, community, and religious organizations, the initiative had the support of two-thirds of Bay State voters in recent polling and had a good shot at passing.

The campaign was spearheaded by the Commonwealth’s two largest unions, Service Employees International Union and Mass Teachers Association. And naturally, most Massachusetts rich people had no intention of letting anyone—let alone a bunch of union leaders, social workers, and priests—raise their taxes.

Flunkies and front groups were then unleashed. The Massachusetts High Technology Council put together a bloc of capitalist lobby groups—including the Massachusetts Taxpayers Foundation, Associated Industries of Massachusetts, and the Massachusetts Competitive Partnership—and challenged the amendment’s constitutionality.

They were aided in this push by the fact that Gov. Charlie Baker, a Republican, was able to appoint five of seven justices to the SJC since taking office in 2015. Including one that, in fairness, wrote the dissenting opinion on the Fair Share Amendment ruling.

Thus, it was no big surprise that the SJC shot the millionaires’ tax down on a legal technicality. Since the wealth lobby had no convincing political argument against the tax beyond “we don’t want to pay it.” But they had high-powered lawyers, plenty of money, and a court stacked in the right direction. Theirs. A capitalist veto in the making.

Professor Lawrence Friedman of New England Law | Boston explained the decision succinctly on a special edition of The Horse Race podcast—hosted by Lauren Dezenski of Politico Massachusetts and Steve Koczela of the MassINC Polling Group:

“What a majority of the court concluded was that this petition didn’t satisfy the requirements of article 48 [of the Mass constitution] for a valid petition that can go before the voters in November. Because it failed what’s called the ‘relatedness’ requirement—the various parts of the petition didn’t relate to each other sufficiently to pass constitutional muster.

“So the three parts of the petition involve the revenue raising measure, the so-called millionaire’s tax, and then two distinct dedications—one to education and one to transportation. And the court essentially said that, except at a very abstract level, those things are not sufficiently related to satisfy the relatedness requirement.”

The minority of the court, for their part, had a very different view. According to Justice Kimberly Budd (joined by Gov. Deval Patrick appointee Chief Justice Ralph Gants, and pardon the legalese here):

“Disregarding the plain text of art. 48, The Initiative, II, § 3, of the Amendments to the Massachusetts Constitution, as amended by art. 74 of the Amendments, which requires that an initiative petition contain ‘only subjects … which are related or which are mutually dependent,’ the court concludes that, in drafting this language the delegates to the Constitutional Convention of 1917-1918 inserted the words ‘or which are mutually dependent’ as superfluous text. … The court goes on to conclude that the people may not express their opinion on a one section, four-sentence petition because it contains subjects that are not related. … That analysis is flawed.”

In plain English, to rather brutally paraphrase further remarks by Friedman on The Horse Race, activists amended the state constitution a hundred years ago to allow the people of Massachusetts to make laws by referendum because even then the legislative process had been captured by corporations and the rich in ways perhaps unforeseen by John Adams when he drafted the document in 1780.

To block the Fair Share Amendment referendum from going on the ballot for a vote is therefore not in the spirit of the sentence at the core of the SJC majority’s case. The court’s pro-business majority focused on the “relatedness requirement.” Its pro-worker minority countered that referendum questions that contain “unrelated” items that are “mutually dependent” pass constitutional muster. But with five votes to two, the majority prevailed.

The result? The tiny percentage of Mass residents who make more than a cool million a year will not see their state taxes rise from 5.1 to 9.1 percent. And the estimated $2 billion that was expected to be raised from that levy annually will not be applied to the Commonwealth’s education and transportation budgets. Both areas that are ridiculously underfunded given our state’s wealth relative to much of the rest of the nation.

Worse still, the spurious myth that the Mass capitalists’ “coalition of the willing” flogged—and continues to flog in the case of the Boston Herald’s ever fact-light columnist Howie Carr—that rich people leave states that increase their taxes will continue to seem like reality to less careful onlookers of the local political scene. Despite the fact that a major study and a book entitled The Myth of Millionaire Tax Flight: How Place Still Matters for the Rich by Stanford University sociology professor Cristobal Young have used big data to dismiss the idea as mere scaremongering, according to Commonwealth magazine.

Now Raise Up Massachusetts has two options: 1) start the referendum process all over again with language that will pass muster with the narrowest and most conservative interpretation of the “relatedness’ requirement,” or 2) take the fight to the legislature.

With the chances of the legislature passing any kind of tax increase being approximately zero as long as Robert DeLeo is House speaker, starting the referendum process again from scratch is pretty much the only way to go.

Unless Raise Up leaders decide to make some kind of “deal” with the legislature. Which I sincerely hope is not the case. Because the whole Fair Share campaign is already a major compromise given that the real goal of any forward-thinking left-wing reformer in this arena has to be the repeal of article 44 of the state constitution that prohibits a graduated income tax system. Followed by the passage of such a system.

While I’m well aware that every attempt to do that has been defeated in the past, I’m also aware that if referendum questions aimed at the much broader goal of winning a fair tax system were on the table, then it would be possible to negotiate for something smaller like the “millionaires’ tax” if the effort ran into trouble.

As things stand, Raise Up Mass appears to have little room to maneuver. So, better to start preparing for a win in 2022 on an improved referendum strategy—preferably aiming for a graduated income tax to replace our anemic flat tax system—than to make a bad deal merely to be able to declare a false “victory” to its supporters and switch its public focus to the two other drives it still has in play: paid family and medical leave, and the fight for a $15-an-hour minimum wage.

Apparent Horizon is syndicated by the Boston Institute for Nonprofit Journalism. Jason Pramas is BINJ’s network director, and executive editor and associate publisher of DigBoston. Copyright 2018 Jason Pramas. Licensed for use by the Boston Institute for Nonprofit Journalism and media outlets in its network.

URBAN MISSION

The solution to UMass Boston’s woes could start with a city-run college

May 9, 2018

BY JASON PRAMAS @JASONPRAMAS

There was an interesting conversation recently between two people who I often criticize for being… um… insufficiently public spirited. The Boston Globe’s Shirley Leung asked Boston mayor Marty Walsh a great question: “What if the city took over the University of Massachusetts Boston?” Walsh, to his credit, replied: “Am I looking to take on a potentially new school? No. … Do I think Boston potentially could be positioned well enough to handle it? Absolutely.”

UMass Boston has been struggling to make ends meet for many years. According to the Dorchester Reporter, union activists at the school say that student tuition and fees, state appropriations, and grants, are actually sufficient to cover its operating costs. But UMB labors under more than $30 million in structural deficit from the cost of belatedly rebuilding a campus that was thrown together with substandard materials by corrupt contractors on top of a landfill back in the 1970s. And a lot of other debt besides.

Successive legislatures and governors have been unwilling to fork over the money to cover the long-needed repairs—sticking a school with an “urban mission” to serve working-class Boston students with a mountain of debt that it can’t clear on its own. Even after controversial longtime chancellor J. Keith Motley was ousted last year and replaced with interim chancellor and state government hatchet man Barry Mills. Who presided over the layoff of dozens of critical faculty and staff in the interest of “balancing the school budget” even though the UMB community is not to blame for its plight.

As the state prepares to bring in a new “permanent” chancellor, it is not prepared to do the right thing. So, it’s definitely worth pushing Walsh to at least produce a serious study on whether a city that struggles to properly fund K-12 education could really do a better job running a medium-sized research university that the Commonwealth can.

It remains to be seen if UMass Boston is too heavy a fiscal burden for the city of Boston to take on. But there is a way that Mayor Walsh could dip his toe into the murky waters of administering a four-year public college without taking over UMB in its entirety. That would be to consider a plan for a separate city college that I had a hand in developing between 2005 and 2007 while I was a student, and then a graduate teaching assistant, at UMB’s College of Public and Community Service (CPCS). It was originally conceived as a possible response to the university’s destruction of that innovative and popular division.

In brief, CPCS was the most diverse college within the most diverse university in the entire Northeast. Not only did it focus on recruiting working-class Boston students from nontraditional backgrounds—like single mothers—it also put a lot of effort into recruiting older working students like me who had never finished college. It was founded in 1972 and 1973 by professors and politicians who believed so strongly in UMB’s urban mission that they developed a college purpose-built to take students from poor city neighborhoods with few opportunities and turn them into stellar university graduates. Which it did with aplomb for over 30 years.

The following section of the CPCS Mission Statement shows how seriously the school took its mandate:

The college works toward overcoming the attitudes, beliefs, and structures in our society which prevent access to the resources that exist and discourage full participation in economic, civic, cultural and political life. As an alternative educational institution, CPCS endeavors to function as an inclusive, democratic, and participatory learning community which promotes diversity, equality, and social justice.

Unfortunately, the administration of a decade ago—led by Motley—decided that the few bucks more it cost per year to educate a CPCS student compared to a “regular” UMB student was too much to spend. And it had deep ideological differences with CPCS pedagogy. Especially the rejection of letter grades as a metric for success. So it killed the college in all but name by 2008. Despite strong protests by its students, staff, and faculty.

Given the current crisis at UMass Boston, Mayor Walsh could revive the plan for a new City College of Boston that myself and other campus activists first suggested… as a successor to CPCS. The goal would be to provide a place for a few hundred working-class native Bostonians at a time. Students who can handle a four-year degree program academically, but are being driven out of UMB by its ever-rising sticker price—and its shift to attempting to compete with local private universities for white suburban middle-class students and full-freight paying foreign students by building dorms. Which is being done, in part, to allow its latest cowardly administration to get rid of its debt load without direct state aid.

The City College could hold classes in existing municipal facilities and start with a few dozen faculty and staff. It would be run by the city of Boston. And ideally, it would strive to charge students no more than the Hub’s two-year community colleges, Bunker Hill and Roxbury… which it should work with closely.

If the new college does decently well for a few years, then maybe the city could take over UMass Boston in its entirety, merge the two, and move on to strengthen its urban mission university-wide. Returning the school to its urban-focused roots… with local sources of funding that are somewhat more receptive to community needs than state funding sources… and a new sense of purpose.

Even such a bold move would not absolve the legislature and the governor of their responsibility to properly fund Mass public higher education as completely as the state budget will allow—rather than doing things like dumping $1.5 billion on the biotech industry—and to lobby the federal government ferociously for more funding as well. But it could at least ameliorate an increasingly dire situation for Bostonians seeking to improve their lot by obtaining a bachelor’s degree. And get the city back in the business of expanding public services rather than privatizing them.

This column was originally written for the Beyond Boston regional news digest show — co-produced by the Boston Institute for Nonprofit Journalism and several area public access television stations.

Note of Appreciation

Big thanks to Bill Marx of Arts Fuse and Greg Cook of Wonderland (and sometimes DigBoston) for inviting me to participate in a great forum “For the Love of Arts Criticism II: Small Magazines and Bloggers” held on Monday at Rob Chalfen’s fabulous music and arts space, Outpost 186, in Inman Square. Props to fellow speakers Chanel Thervil of Big Red & Shiny; Pat Williams of the Word Boston; Heather Kapplow of, like, everywhere, including DigBoston; Franklin Einspruch of Delicious Line (and DigBoston); Marc Levy of Cambridge Day; Oscar Goff and Chloé DuBois of Boston Hassle; Dave Ortega of the Somerville Media Center; Jameson Johnson of Boston Art Review; Lucas Spivey of Culture Hustlers podcast; Rick Fahey of On Boston Stages; Suzanne Schultz of Canvas Fine Arts; Olivia Deng of several publications, including DigBoston; noted events producer Mary Curtin; Aliza Shapiro of Truth Serum Productions; former Boston Phoenix, Improper Bostonian, and Boston Magazine writer Jacqueline Houton; and a number of other folks. Read Greg Cook’s fine article on the proceedings for all the details at gregcookland.com/wonderland.

Apparent Horizon is syndicated by the Boston Institute for Nonprofit Journalism. Jason Pramas is BINJ’s network director, and executive editor and associate publisher of DigBoston. Copyright 2018 Jason Pramas. Licensed for use by the Boston Institute for Nonprofit Journalism and media outlets in its network.

TOWNIE: AIRLINES SUING, UMASS SCREWING

Corporate attack on workers rights and a corporate-style attack on UMB by UMA

April 11, 2018

BY JASON PRAMAS @JASONPRAMAS

If there’s one thing I think people should do every day, it’s read the business press. Because that’s where you see how the world runs. A world that naturally includes Massachusetts.

Airlines sue Mass over sick time law

Case in point, Airlines for America—a coalition that includes JetBlue Airways, United Airlines, American Airlines, and several other carriers, according to the Boston Globe business section—sued Mass Attorney General Maura Healey last week over a 2015 law that guarantees sick leave to many Bay State workers. Including airline employees. “Now surely,” you’re all doubtless thinking, “an industry that wouldn’t exist were it not for decades of massive government subsidies couldn’t possibly consider doing anything that might hurt its workers by attacking a government program that helps them.” But no, the airlines are totally doing that. It’s what big corporations always do to their workers. Along with endless union busting.

According to the Mass.gov Earned Sick Time page, the law states that most workers “in Massachusetts have the right to earn and use up to 40 hours of job-protected sick time per year to take care of themselves and certain family members. Workers must earn at least one hour of earned sick leave for every 30 hours worked.” It further states that employers “with 11 or more employees must provide paid sick time. Employers with fewer than 11 employees must provide earned sick time, but it does not need to be paid.” Employers can “ask for a doctor’s note or other documentation only in limited circumstances.”

The airlines are basically trying to argue—in the fashion of sadly deceased comic Phil Hartman in the role of Unfrozen Caveman Lawyer—that the Mass sick time law “frightens and confuses” them. And that with all the billions of dollars they either gouge out of travelers or simply have the federal government hand them whenever they cry poverty, they can’t possibly figure out how to sync up all their various state, national, and international sick time laws they’ve already handled for decades with the Commonwealth’s more decent law. Despite, you know, computers.

Bottom line, they want an exemption from the law to make slightly bigger profits and escape regulation, and they’re suing Healey to get their way. Claiming it’s unconstitutional and shouldn’t apply to airlines. The same thing they did in Washington State in February, according to the Seattle Times.

The AG should have fun with this one. But readers can give her a hand by calling up the airlines and their front group and telling them to stop attacking the Commonwealth’s sick leave program.

UMass Boston suffers more cuts while UMass Amherst buys Mount Ida College

A couple of related developments in the UMass system over the last several days. First, UMass Amherst is buying the private Mount Ida College in Newton for $37 million, according to WBUR. It plans to use the campus as a base for Boston-area internships and co-ops for its students. The school will also assume Mount Ida’s debt of up to $70 million.

The situation is widely viewed as an unfortunate attack on UMass Boston turf by the more “elite,” better-funded, and melanin-challenged UMass Amherst. With UMB faculty, staff, and students; higher ed experts; and the editorial boards of publications from the Boston Globe to the Lowell Sun asking why it’s necessary for UMA to spend big money on a separate suburban campus to connect its students to Boston. Especially given that there’s already the perfectly good but woefully underfunded UMass Boston campus in the city itself. Which could certainly use an injection of tens of millions of dollars from any source of late.

Speaking of which, second, UMass Boston is slashing the budget of 17 of its research centers by $1.5 million, including the famed veteran-focused William Joiner Institute for the Study of War and Social Consequences, as part of its attempt to get out from under the $30 million in mostly new construction-related deficit it’s been saddled with by a state government that insists on running its colleges like individual businesses. Rather than branches of a single statewide public service.

It’s worth mentioning, as I do on a regular basis, that we need to move the state and nation to the kind of fully public higher education system that many other countries have. Which spends sufficient tax money to guarantee every US resident a K-20 education. And tells private schools like Harvard that they can only remain private if they stop taking public money.

That’s the only way we’re going to stop this kind of spectacle. Where two parts of the same state public university system—one, Amherst, that primarily serves middle-class white suburban students, and one, Boston, that primarily serves working-class urban students of color—work at cross-purposes to one another. Amherst with a larger budget, and Boston with a smaller one. Separate and unequal.

For the moment, readers can help out by joining me in signing the petition to save the William Joiner Institute at change.org. And those so inclined can protest the Mount Ida College sale to UMass Amherst at the Board of Higher Education meeting on April 24. But I think critical calls and emails to UMass President Marty Meehan will likely be most effective. You can find his contact page on the massachusetts.edu website.

Check out TOWNIE EXTRA: YASER MURTAJA, PRESENTE! here.

Townie (a worm’s eye view of the Mass power structure) is syndicated by the Boston Institute for Nonprofit Journalism. Jason Pramas is BINJ’s network director, and executive editor and associate publisher of DigBoston. Copyright 2018 Jason Pramas. Licensed for use by the Boston Institute for Nonprofit Journalism and media outlets in its network.

TOWNIE: MASS REGIONAL TRANSIT AUTHORITIES FACE MAJOR BUDGET CRISIS

Gov. Baker’s proposed cuts throw gasoline on raging policy fire

February 21, 2018

BY JASON PRAMAS @JASONPRAMAS

A quarter-century ago, I lived in Lawrence for a few months. Because it was the closest place to Boston that I could find a cheap apartment on short notice. Unfortunately, I had a low-paying job in the city and couldn’t afford a car. So I took the commuter rail over an hour each way back and forth whenever I had a shift. Then at the end of the day, I was faced with getting to my apartment a couple of miles away from the station. Merrimack Valley Regional Transit Authority (MVRTA) bus service ran near my place. But even in the early 1990s with a state budget that looks more humane in retrospect, it was infrequent at best. And my bus dropped me off a few blocks away from where I lived when it was running.

Now that was during rush hour on a weekday. If I got home later than early evening—especially on weekends—MVRTA buses had already stopped running. I moved there in December. And until I moved back to Boston the following March, through what proved to be a very cold winter, I would often get off my train, watch all but a handful of people get into waiting cars and leave, and then begin the long, frozen slog home. Across the Merrimack River, on sidewalks that were mostly unshoveled and roads that were indifferently plowed.

Standing in the middle of Duck Bridge one Sunday night in mid-February during a fierce snowstorm, I experienced a moment of nearly perfect alienation. The scene was completely desolate. No vehicles were on the road. It was pitch black except for the occasional street light with the darker black of largely abandoned textile mills looming in the middle distance. Snow was piling up all around me. The brutal wind off the water cut through my coat. My sneakers were entirely insufficient to the task of keeping me consistently upright—let alone keeping my feet warm and dry. And I remember thinking that if I had slipped and fallen into the river, no one would have the slightest idea of where I’d gone until spring. Because in the era before ubiquitous cell phones or texters, I could not have typed “aaaaaaah” to my girlfriend as I fell. So who would be the wiser?

Fast-forward to this week, and that memory immediately sprang to mind when I read the transportation section of Gov. Charlie Baker’s annual state budget proposal. And discovered that he’s planning to level-fund the 15 regional transit authorities (RTAs) for $80.4 million, according to the Mass Budget and Policy Center, while most Bostonians are focusing on the ongoing fight to keep the MBTA solvent. Authorities like the Merrimack Valley Regional Transit Authority… which is already cutting back bus, van, and Boston commuter service and eliminating that Sunday service I kept missing in the early ’90s. Since level-funding means a budget cut, given annual cost increases. And it’s not looking like the legislature is likely to swoop in to save the RTAs later in our now-normalized austerity budget process.

After all, if the legions of working- and middle-class Bostonians that rely on public transit can’t yet force elected state officials to properly fund the MBTA, the smaller numbers of riders in outlying cities like Brockton, Fitchburg, Lowell, and Lawrence are in even worse straits. Especially when many of them are immigrants who can’t vote.

Yet the need for public transit gets more dire the farther you get from Boston. If you don’t have a car in places like Athol, Greenfield, Holyoke, and Pittsfield, literally your only inexpensive transit option is bus service run by your regional transit authority. Which I’ve already made quite clear is of limited usefulness at the best of times. RTAs don’t go everywhere riders need to go and don’t run many of the times riders need to use them. As I experienced during my brief, unpleasant Lawrence sojourn.

People without cars in the many parts of the state that aren’t reached by the MBTA’s main bus and subway lines are already at a major disadvantage in terms of their ability to access jobs, laundry, shopping, education, social services, daycare, and healthcare in the best of times. If RTA service continues to be whittled away year by year, eventually there will be no public transportation left in many locales. And taking an Uber or Lyft won’t be an option for people that can’t even afford a hike in bus fare. Even while those private transportation services are angling to replace public transit for those that can pay their largely unregulated fares.

That is no minor problem—lest readers think that only small numbers of people lack cars in Mass cities outside of the Boston metro area. It’s a major crisis. For example, according to a Governing magazine article looking at car ownership in US cities with a population over 100,000, 19.3 percent of Worcester households and 22.2 percent of Springfield households did not have a car in 2016. Meanwhile, my colleague Bill Shaner at Worcester Magazine just reported that “[t]he Worcester Regional Transit Authority Advisory Board voted to send proposed service cuts to a public hearing after decrying the possible changes as a ‘death spiral’ for the bus system.

He continued, “WRTA officials unveiled several possible measures to bridge a $1.2 million budget gap, due mostly to budget cuts to the RTA system at the state level. The possible measures include routes cut wholesale, cut weekend service, and diminished routes, which would increase wait times between buses.”

Both WRTA Board Chairman William Lehtola and WRTA Administrator Jonathan Church agreed that the system would “cease to exist in a few years” if the funding crisis continues unabated.

Meanwhile, the Republican reported that Springfield RTA “the Pioneer Valley Transit Authority has proposed a 25 percent across-the-board increase in fares and pass prices and a slate of service cutbacks, all to take force July 1.”

So make no mistake, this is a significant escalation in the war on Mass working families by Baker and any legislators that back similar cuts to public transit around the state. Cuts that RTAs have already been struggling with for years. As with the battle to save the MBTA and other public services, the RTAs can only be defended with a concerted fight from their riders. Whose goal must be to increase taxes on corporations and the rich in the Commonwealth, and to change state and local budget priorities to better serve the needs of all Mass residents.

Failing that, you’ll see a lot more people walking long distances in inclement weather statewide. And all too many of them won’t be able to escape their “transit desert” like I did. They will simply become more and more isolated. Until they literally disappear. The way I feared doing on a lonely bridge in the depths of a Merrimack Valley winter half a lifetime agone.

Townie (a worm’s eye view of the Mass power structure) is syndicated by the Boston Institute for Nonprofit Journalism. Jason Pramas is BINJ’s network director, and executive editor and associate publisher of DigBoston. Copyright 2018 Jason Pramas. Licensed for use by the Boston Institute for Nonprofit Journalism and media outlets in its network.

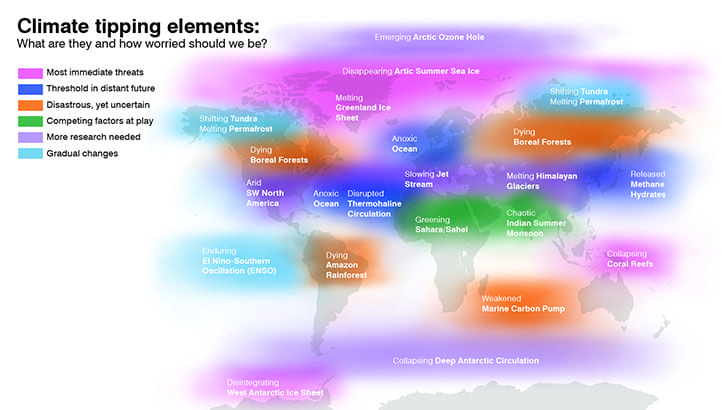

SEA LEVEL RISE IS JUST ONE OF BOSTON’S WORRIES

As Earth approaches several catastrophic global warming “tipping points”

January 24, 2018

BY JASON PRAMAS @JASONPRAMAS

Before writing more columns examining Boston city government’s emerging plans to cope with the effects of global warming, I think a quick review of what area residents are likely to face in the coming decades is in order. Because it’s important to disabuse people of the idea that we’re dealing with “just” a handful of significant problems over time—a rise in air temperature, an increase of extreme weather events, and a rise in sea level—that those problems are isolated to just Boston or the United States, that they are going to continue until the end of the century and then stop, and that there are some simple things we can do to prevent those problems from becoming unmanageable.

The reality is far more frightening. According to Mother Jones, “In 2004, John Schellnhuber, distinguished science adviser at the Tyndall Centre for Climate Change Research in the United Kingdom, identified 12 global-warming tipping points, any one of which, if triggered, will likely initiate sudden, catastrophic changes across the planet.”

There’s been much research and debate since that time about which systems can be considered tipping points and which ones need more research before we can be sure, but the Environmental Defense Fund has a page on its website with an overview of the latest science. It’s called “Everything you need to know about climate tipping points” and you should read it in full. But here’s a quick summary of the tipping points that the Earth is passing or on its way to passing. Largely due to humans continuing to burn CO2-producing oil, gas, and coal decades after it was known to be suicidal to do so.

1) Disappearance of Arctic Summer Sea Ice

The poles are warming faster than the rest of the planet. In the Arctic, sea ice has been melting much more quickly than it used to for much more of every year as the average global temperatures rise year after year. Scientists are now predicting ice-free Arctic summers by mid-century. The less of the year that ice covers the Arctic, the less sunlight is reflected back to space. Sunlight that is not reflected warms the Arctic Ocean, leading to other problems and more global warming overall.

2) Melting of the Greenland Ice Sheet

Of particular concern to Bostonians because of our relative proximity to Greenland, the melting of its ice cap may continue for the next few hundred years until there is none left. Unlike melting sea ice that doesn’t add water to the world’s oceans, melting ice from land does. This will ultimately result in global sea level rise of up to 20 feet, and the process is underway.

3) Disintegration of the West Antarctic Ice Sheet

This tipping point may already have been passed—with the West Antarctic ice sheet already starting to collapse. Like the Greenland ice sheet, it too is expected to take hundreds of years to finish melting, but when it does it could raise the global sea level up to 16 feet.

4) Collapse of Coral Reefs

With oceans already warming and becoming more acidic, the algae eaten by the coral that make up the world’s often huge and spectacular reefs is being jettisoned, resulting in coral bleaching. This process weakens the coral and hastens its death. Which is accelerating the destruction of marine spawning and feeding grounds globally with dire consequences for many nations whose economies rely on them—and for biodiversity. Scientists now predict that the remaining coral reefs will collapse before there is rise in the global temperature of 2 degrees from the old normal average. Most climate models show the world reaching that threshold before the end of this century.

Beyond these, there are several other expected tipping points being studied: the disruption of ocean circulation patterns from the massive influx of fresh water from melting ice (especially in the North Atlantic, which would play havoc with Boston’s climate), the release of marine methane hydrates (which would accelerate the global warming already being caused by the CO2 emissions considered the main cause of climate change), ocean anoxia (a process creating growing oxygen-deprived “dead zones” in our oceans that can no longer support most life, aka “bye bye seafood”), the dieback of the Amazon rainforest (caused by human activity like cutting down huge numbers of trees with devastating consequences for biodiversity coupled with the loss of a major CO2 sink), the dieback of the boreal forests (still being studied, but means the death of more vast forests in and around our latitude of the planet), the weakening of the marine carbon pump (the Earth’s oceans have been absorbing much of the excess carbon in the atmosphere, but through this process will become less effective at it), the greening of the Sahara (some positive effects would come from this, but many basic ocean life forms rely on nutrients from the desert sand blowing into the ocean and will be negatively affected by losing it), and the increasingly chaotic Indian summer monsoons (could result in extensive drought in one of the Earth’s most populous regions).

Other processes underway may also be potential tipping points, including the collapse of deep Antarctic ocean circulation, the appearance of an Arctic ozone hole (joining the existing Antarctic ozone hole in causing rising UV levels in the Arctic with various negative effects), the aridification of the US Southwest (as moisture moves to the upper Great Plains), the slowdown of the jet stream (which could leave more weather systems stuck in place for weeks at a time, including extreme systems like our recent polar vortex-induced cold wave, among other negative effects), the melting of the Himalayan glaciers (which help provide fresh water for much of South Asia’s population), a more permanent El Niño state (which could result in more drought in Southeast Asia and elsewhere), permafrost melting (which results in more CO2 and methane being released, accelerating global warming further), and tundra transition to boreal forest (with uncertain effects).

Adding the above to the general effects of global warming that we’re already experiencing—areas that got lots of rain getting less and areas that got little rain getting more rain storms for more of the year, hotter temperatures overall leading to an array of bad effects like tropical diseases moving north, and the “sixth extinction” of large numbers of species of animals and plants—and keeping in mind that this is happening everywhere around the planet, readers should understand that we’re not facing a localized crisis.

And remember, all the processes mentioned above are interlinked in complex ways that are absolutely not fully understood by our current science.

So Boston is not just going to “trial balloon and town hall meeting” its way out of this array of existential crises. Surviving even one of the major problems caused by global warming—like the flooding from rising sea levels I wrote about last week—is going to be very difficult… and very expensive. And who’s going to pay for it? Well, going forward, in addition to pointing out that we’ll have to devote an ever-increasing percentage of public budgets to these problems, expect me to call for the corporations that started and continue to profit from global warming—the oil, gas, and coal companies—to pay for cleaning up the mess they created. To the degree possible. Which might not be sufficient to the monumental tasks at hand.

Still, it will be critical for Boston to join municipalities like New York City in suing the carbon multinationals Exxon, Chevron, BP, Shell, ConocoPhillips, and others for redress. While divesting the city from all investments in those companies’ stocks. And suing, and ultimately deposing, governments like the Trump administration that are aiding and abetting these corporations’ destruction of the planet.

Failing that, Boston and all of human civilization is literally sunk… burned… and perhaps ultimately suffocated. Dying not with the bang of nuclear war—itself a fate we also need to organize immediately to avoid given the federal government’s return to atomic sabre rattling—but with an extended agonizing whimper.

It’s up to all of us to stop that from happening.

Apparent Horizon is syndicated by the Boston Institute for Nonprofit Journalism. Jason Pramas is BINJ’s network director, and executive editor and associate publisher of DigBoston. Copyright 2018 Jason Pramas. Licensed for use by the Boston Institute for Nonprofit Journalism and media outlets in its network.

THE SEAPORT FLOOD IS JUST THE BEGINNING

Unless Boston builds proper defenses against global warming-driven sea level rise

January 17, 2018

BY JASON PRAMAS @JASONPRAMAS

So, Boston’s Seaport District flooded early this month during a bad snowstorm in the midst of several days of arctic temperatures. And nobody could be less surprised than me. Because I’ve spent a lot of the last quarter century closely following developments in the science of climate change. And the “bomb cyclone” that caused the flooding, and the polar vortex that caused that, are both likely to have been caused by global warming. Yale University Climate Connections just produced a great video that features several luminary climate scientists explaining why at yaleclimateconnections.org. Definitely check it out.

No question, though, that it’s good to live in a region where local government at least recognizes that global warming is a scientific reality. The city of Boston is certainly ahead of most municipalities in the US in terms of laying plans to reduce greenhouse gas emissions enough to become “carbon neutral” and to deal with some of the anticipated effects of climate change. Particularly, flooding from inexorably rising sea levels and increasingly powerful and frequent storms. Which the more reactionary Boston TV newsreaders still insist on calling “wild weather.” But its plans are largely just that… plans. And they are still incomplete and, frankly, woefully inadequate to deal with the magnitude of the crisis facing us all.

Boston city government has initiated an array of climate change initiatives, including Greenovate Boston, a section of the Imagine Boston 2030 process, and—most germane to this discussion—Climate Ready Boston. They are all producing very nice reports grappling with some of the challenges to humanity presented by global warming in the decades to come. But the reports are written by planners and experts who are clearly pulling their punches for reasons that remain somewhat opaque. And in doing so, any good that might come out of the reports and the policy actions that will result from them is essentially undone.

A look at metro planning on global warming-induced flooding is a good way to illuminate the problem in question. The Climate Ready Boston program released a 340-page report in December 2016 that was meant to be a comprehensive assessment of the threats presented to the city by global warming—with plans for possible correctives. It does mention the idea of building giant dikes, storm barriers, and retractable gates (which they call a “harbor-wide flood protection system”) across Boston Harbor as the method with the most potential to save much of the city from major flooding. Which makes sense since Mayor Marty Walsh signed a 2015 agreement with Dutch officials to work together to manage rising sea levels, according to Boston Magazine. And the Dutch are recognized world experts on giant storm barriers and hydroengineering in general, lo, these last few hundred years.

But there’s no firm commitment for harbor-wide defenses in the report. Yet it should be obvious that they are absolutely necessary if Boston is going to continue as a living city for even a few more decades. At least Amos Hostetter of the Barr Foundation—who is a major player in Boston’s climate efforts—put up $360,000 for the UMass Boston Center for the Environment to study their feasibility last year, according to the Boston Globe.

More concerning than its waffling on building big dikes, the big Climate Ready Boston report chooses to focus on the possibility of sea level rise of no more than 3 feet by 2070—although it allows that a rise of 7.4 feet is possible by 2100:

The highest sea level rise considered in this report, 36 inches, is highly probable toward the end of the century if emissions remain at the current level or even if there is a moderate reduction in emissions. … If emissions remain at current levels, there is an approximately 15 percent chance that sea levels will rise at least 7.4 feet by the end of century, a scenario far more dire than those considered here.

Similar caution is on display with an October 2017 Climate Ready Boston report called “Coastal Resilience Solutions for East Boston and Charlestown”—focusing on tactics to protect two Boston neighborhoods on Boston Harbor at high risk for flooding caused by global warming. Once again, the authors’ assumption is that global warming-related sea level rise in Boston will be no more than 3 feet higher than year 2000 figures by 2070. Even though such estimates—which we have already seen are conservative by Climate Ready Boston’s own admission—also indicate that we could face 7-plus feet of sea level rise or more by 2100. And even higher rises going forward from there. Because sea level rise is slated to continue for generations to come.

What’s weird about such methodological conservatism is that a 2016 paper in the prestigious science journal Nature co-authored by a Bay State geoscientist says the lower figures that all the city’s climate reports are using already look to be wildly optimistic.

According to the Boston Globe:

“Boston is a bull’s-eye for more sea level damage,” said Rob DeConto, a climate scientist at UMass Amherst who helped develop the new Antarctica research and who co-wrote the new Boston report. “We have a lot to fear from Antarctica.” … If high levels of greenhouse gases continue to be released into the atmosphere, the seas around Boston could rise as much as 10.5 feet by 2100 and 37 feet by 2200, according to the report.

What’s even weirder is that the same UMass scientist, Rob DeConto, co-authored a detailed June 2016 report for Climate Ready Boston called “Climate Change and Sea Level Rise Projections for Boston: The Boston Research Advisory Group Report” with 16 other climate scientists that look at an array of possible outcomes for the city—and include a discussion of the higher sea level rise figures mentioned in the Nature paper. The report concludes with an admission that current science doesn’t allow for accurate predictions of climate change in the second half of the century. All the more reason, one would think, that models predicting higher than anticipated sea level rise should not seemingly be dismissed out of hand in other Climate Ready Boston reports.

The Globe also reported that a study by the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) says Boston can expect a sea level rise of 8.2 feet by 2100. Both 8.2 foot and 10.5 foot estimates are higher than the 7.4 foot estimate that Climate Ready Boston says is possible by 2100, and well above the 3 feet that it is actually planning for by 2070.

The same team that produced the larger Climate Ready Boston report authored the East Boston and Charlestown report; so they are doubtless quite well-aware of all this. Which is evident in this sentence about the (insufficient) extensibility of their proposed neighborhood-based flood defenses: “If sea levels rise by more than 36 inches, these measures could be elevated at least two feet higher by adding fill, integrating structural furniture that adds height and social capacity, or installing deployable flood walls. With this built-in adaptability, their effectiveness could be extended by an additional 20 years or more.”

The point here is not that the Boston city government is doing nothing about global warming-induced flooding. It’s that the city is potentially proposing to do too little, too late (given that most of the flood defenses it’s proposing will remain in the study phase for years, and many will protect specific neighborhoods but not the whole city when finally built), for reasons that aren’t entirely clear. Though it’s probable that those reasons are more political and economic than scientific. Avoiding scaring-off the real estate developers and major corporations that provide much of the current city tax base, for example. The kind of thing that will make life difficult for politicians who then make life difficult for staffers and consultants working on global warming response plans.

Regardless, if experts like the Dutch are basically saying, Boston really needs to build the biggest possible harbor-wide flood protection system to have any hope of surviving at least a few more decades, then we can’t afford to do one of the more half-assed versions of the big cross-harbor storm barrier plan mentioned in the original Climate Ready Boston report—or, worse still, fail to build major harbor-wide defenses at all. If major studies by climate experts are saying that 3 feet of sea level rise by 2070 and 7.4 feet by 2100 are overly optimistic figures, then we need to plan for at least the highest reasonable estimates: currently, the NOAA’s 8.5 feet or, better yet, the Nature paper’s 10.5 feet for the end of the century. It’s true that we could get smart or lucky and avoid those numbers by 2100. But what about 2110? Or 2150? Or 2200? Sea level rise is not just going to stop in 2070 or 2100.

Are city planners and researchers willing to gamble with the city’s fate to avoid sticky political and economic fights? Let’s hope not. For all our sakes. Or the recent Seaport District flood—and numerous other similar recent floods—will be just the start of a fairly short, ugly slide into a watery grave for the Hub.

Apparent Horizon is syndicated by the Boston Institute for Nonprofit Journalism. Jason Pramas is BINJ’s network director, and executive editor and associate publisher of DigBoston. Copyright 2018 Jason Pramas. Licensed for use by the Boston Institute for Nonprofit Journalism and media outlets in its network.

TOWNIE: UMB DRUBBING, PAWSOX GRUBBING

University cuts and a (possible) corporate scam just in time for the holidays

November 27, 2017

BY JASON PRAMAS @JASONPRAMAS

UMass Boston admin lays off more staff, unions push back

The neoliberal war on public higher education continues unabated in Massachusetts as the UMass Boston administration announced the layoff of 36 personnel last week, and a reduction in hours for seven more. According to the Boston Globe, all of them are “staff who clean the school, help run academic programs, work in the student health office, or in other ways support the daily operations of the university. Some have worked there more than 30 years.” UMB had 2,095 employees in 2016, but has cut 130 jobs so far this year. The university serves over 16,000 students.

As of this writing, campus unions are planning protests. Hopefully, such actions will ultimately build a political movement capable of operationalizing the prescriptions of the fine report a coalition of UMB “students, staff unions, and faculty” released in September. Entitled “Crumbling Public Foundations: Privatization and UMass Boston’s Financial Crisis,” it lays the responsibility for the budget crisis currently engulfing the university at the feet of the UMB administration, the UMass Board of Trustees, and the state legislature.

As well it should. The legislature has been slashing the state higher ed budget since the 1980s. The board keeps raising the tuition and fees paid by students and families to cover the resulting gap. And the UMB administration continues increasing the number of high-level administrators with questionable job descriptions and fat paychecks who somehow rarely face layoffs—despite costing the school far more per capita than each of the low-level employees who keep getting axed of late. All while expanding the campus in ways that don’t always benefit the urban students that institution was built to serve… running up unsustainable debt loads in the process.

The report calls for five major reforms that its authors believe would set the campus to rights:

- UMass Boston should not be required to show a positive net income in its budget. Instead, it should be allowed to make debt payments using the reserves it’s been forced to build up for the last few years—and the Board of Trustees should “release Central Office reserves” to help with those payments. Rather than compelling students and their families to shoulder such costs through ever-increasing tuition and fees.

- The UMB administration should engage in an open and transparent planning process with faculty, staff, and students that will “ensure that the campus can continue to provide an affordable and diverse education along with appropriate support services to its students,” review interest and principal payments, and review the rapid increase in high-level administrator expenses.

- The UMass Board of Trustees should endorse the Fair Share Amendment that will levy an additional 4 percent income tax on millionaires and spend the money on public higher education, pre-K-12 education, and transportation if passed by binding statewide referendum next year.

- The Mass Legislature should cover the cost of rebuilding crumbling campus infrastructure.

- The Mass Legislature should annually increase appropriations for public higher education until we are at least on par with the national average based on our state’s wealth. The Commonwealth is presently at the bottom of the pack for state appropriations for public higher ed.

The white paper concludes with a visionary sentiment that’s worth reprinting in full: “In considering these recommendations, we ask that we all—members of the Massachusetts legislature, the UMass Board of Trustees, UMass Boston’s administration, and the larger community of Boston—remember the purpose with which we are tasked. Chancellor John W. Ryan, at UMass Boston’s 1966 Founding Day Convocation, reminded those gathered that ‘we have an obligation to see that the opportunities we offer… are indeed equal to the best that private schools have to offer.’ This is the expectation that the citizens of our Commonwealth have for themselves and their family members when they come to UMass Boston. This is the responsibility that UMB staff, faculty, and administrators take on each day on behalf of our students. This should be what guides the decision of the Board of Trustees and the Mass legislature as we work to address the crisis at UMB.”

PawSox Worcester visit: boondoggle in the making?

Meanwhile, in faraway central Mass, my Worcester Magazine colleague Bill Shaner is tracking what could be another big giveaway of local and state money. Seems that the Pawtucket Red Sox—the BoSox Triple A affiliate team—have been courting Worcester for a few months and might be looking to move there in exchange for lashings of public lucre. Shaner reports that multiple sources said that Jay Ash, secretary of Gov. Baker’s Executive Office of Housing and Economic Development, attended a meeting last week between Worcester officials and PawSox bigs. Though “City and PawSox officials both declined to comment on the meeting, or whether or not it took place.” While “Ash’s staff confirmed he was in Worcester Monday but couldn’t say what for.” All I can say for now is that, like some capitalist Santa Claus, whenever Ash appears corporate leaders can virtually always expect a yuuuuge present from the Bay State and any municipal government in range in the near future. So this nascent Woo-town deal is definitely worth watching.

Townie (a worm’s eye view of the Mass power structure) is syndicated by the Boston Institute for Nonprofit Journalism. Jason Pramas is BINJ’s network director, and executive editor and associate publisher of DigBoston. Copyright 2017 Jason Pramas. Licensed for use by the Boston Institute for Nonprofit Journalism and media outlets in its network.