And I know that because his Boston University administration expelled me for participating in nonviolent student anti-apartheid protests in 1986

Recently, CommonWealth Magazine published an opinion piece by Rachel Silber Devlin, the daughter of former Boston University Chancellor John Silber, who published a book about her father last year and is giving a talk about him at BU today.

Her article paints a picture of a man who “always believed strongly in the rights of each individual and was protecting the constitutional rights—freedom of speech and freedom of assembly—of those who were trying to participate in the public discussion of issues.” And clearly seeks to link her distaste for individuals and organizations who seek to shut down civil debate rather than encourage it to her father’s views and practices. Which is obviously her prerogative.

However, although I’m not in the habit of speaking ill of the dead, I must disagree with Silber Devlin that John Silber was the model of the enlightened academic leader who encouraged reasoned debate and “had an idea of activism as an activity that was respectful of the constitution and not destructive.”

To anyone who didn’t agree with him on the sprawling campus he ran for more than three decades, John Silber repeatedly did precisely what his daughter says he inveighed against as an intellectual in her CommonWealth essay: He used the power of his office and the significant resources at his disposal to “shout his opponents down” (generally in fora in which they were never afforded the courtesy of a reply) and he regularly resorted to using “brute strength” to stifle his opponents’ voices on campus—thus demonstrating time and time again that he definitely believed that “might makes right.”

As was the case when he threw me out of Boston University in June 1986 for what was absolutely protected speech activity.

At the time, I was a undergraduate communications major in the BU College of Communication (called the School of Public Communication when I started college in August 1984) and a member of the Boston University Southern Africa Task Force, the student organization working with like-minded staff and faculty to push the school to fully divest of all its investments in the then-racist state of South Africa. For over a year before I joined the group in spring 1985, its members had tried to engage the BU administration in open debate on John Silber’s stance (a common one among powerful American corporate and political leaders of the time) of continuing to do business with the rogue nation where a small white minority kept its Black majority oppressed by its “apartheid” (apartness) system of legalized racial discrimination.

Silber and his administration resolutely refused to interact with us in any meaningful way. Instead, they did to us what they did to any student organization that was a thorn in their side. They ensured that the Student Activities Organization—which they had created to take something like half of the money raised from students from the mandatory Student Activities Fee we were made to pay (on top of the already ridiculously high tuition and fees we had to pony up annually) and use those funds to pay a bureaucracy to disburse the other half of the money—blocked us from receiving operating funds, an office, and the right to reserve campus facilities for our events. Emoluments of the very type that the Silber administration lavished upon conservative student organizations.

The same illiberal treatment was meted out to an array of (actual) liberal, left-wing, and human rights organizations. Notably, the genuinely independent, donation-funded, campus newspaper bu exposure (formerly the newsletter of the banned Student Union, the independent predecessor student government to the administration-controlled Student Senate, that the Silber administration defunded during the failed 1976 campus upheaval aimed at his ouster) that I also worked on along with colleagues from many effectively banned student groups.

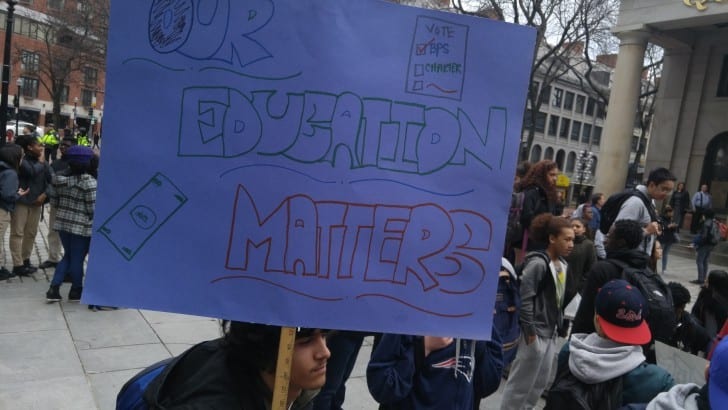

Such anti-democratic measures did backfire, however. Leading to a significant campus anti-apartheid protest movement by fall 1985 that ultimately involved hundreds of students by the following spring. Our tactics were the tactics of nonviolent political movements in the tradition championed by BU’s most famous alumnus, Martin Luther King, Jr. And indeed many of our rallies were held at the university’s MLK Plaza because the kind pastors that ran the campus chapel controlled it, if memory serves.

The SATF held an array of educational events. We leafletted the campus community and passers-by constantly in those pre-Internet and pre-cellphone days. Howard Zinn, famed historian and longtime BU professor (himself having suffered greatly at the hands of Silber and his administration on numerous occasions), let us take over his 300-person class that I was taking in the spring 1986 semester at least twice to talk to that sizeable group of students about our campaign. Students from across the political spectrum, I hasten to add, since Zinn’s class was widely known to be the only place on campus where free speech was actually allowed. No accident that the class was held off campus (though surrounded by it) in a Nickelodeon movie theater.

We built a coalition that included many BU student organizations and the staff and faculty labor unions in favor of divestment. We held dozens of protest actions small and large. Twenty of us even went on hunger strike in late March 1986—for eight days in my case. A period in which I remember Rachel Silber Devlin’s father making a number of particularly unkind remarks about us in the campus and regional media.

And what did John Silber and his Boston University administration do in response to our activities during that 1985-1986 school year? They used the BU police force that Silber had armed previously in the face of much dissent to drive us out of public spaces on our own campus. Public spaces we had every right to be in.

For example, just prior to the protest that prematurely ended my brief BU sojourn, the SATF held a “study-in” on the first floor of BU’s main library—with strong support from the librarians, it must be said. After a few days, the Silber administration had its police remove us from the library. Our own library. Where we blocked no one and interfered with no one else’s ability to study or learn. We were simply present and bore witness to the need to overturn what we believed (correctly, I still maintain) was an unjust university policy.

Every time our SATF or any other student group held any kind of left-leaning protest action anywhere on (or at times, just off-) campus, Silber or any number of his powerful (and handpicked) vice-presidents or department heads would send the BU cops in to roust us. And there were many opportunities to protest, because John Silber invited a steady stream of leaders from reactionary governments around the world (South Africa prominently included) to be feted at significant university-sponsored events. While anyone “to the left of Attila the Hun,” as I liked to quip sardonically in that period, who had the global standing to debate such worthies was very pointedly not afforded the same courtesy.

I could go on sketching my own portrait of BU campus life in the mid–1980s at some considerable length, but to arrive at my point, what my fellow student activists and I most assuredly did not do was shut down anyone else’s ability to speak or debate. To the contrary, SATF members spent much of our time trying to get the Silber administration to really engage in dialogue with us rather than trying to simply continue to dismiss our growing ranks as unrepresentative of the student body. Only to be rebuffed at every turn. Hence, our divestment campaign was forced to focus more and more on protests.

As March turned to April, then, we decided to hold a thought-provoking educational action that was being used by anti-apartheid activists on campuses across the US that school year—a tactic we had attempted before in front of the College of Communication building on October 10, 1985. But the BU police had quickly dismantled it.

For our second try, we secretly (or so we thought) built the frames of a few shacks that we meant to symbolically represent the “shantytowns” that Black South Africans were often forced to live in as they toiled in an array of menial, low-paid, jobs to which they were restricted. Surrounded by heavily armed police and military units as a primary means of social control. Endlessly hectored and harassed by the powerful South African government, backed by the US as it was throughout the still-hot Cold War. Too often unto death throughout the decades of the apartheid regime.

Just before the day of our planned protest, the BU police somehow found our shack frames and illegally tossed them … much in the way that campus janitors were caught illegally dumping entire stacks of our bu exposure newspapers in the trash on numerous occasions. As a result of what? High spirits? Acting without orders (ha!)? Who can say, right?

We managed to prepare new shack frames and on the morning of April 24, 1986, we arrived in front of the George Sherman Union to find BU police and right-wing department heads College of Communication Interim Dean and International Relations Department Chair H. Joachim Maître and College of Communication Assistant Dean Ronald Goldman already waiting for us—the two high-ranking academicians (who even then were quite controversially overseeing a mysterious federal government-backed “Afghan Media Program” to train the kind of fundamentalist Muslim guerillas that now run Afghanistan as “journalists”) loudly mocking us as we unloaded our materials.

And the moment we started setting up our shacks, not blocking a single entrance of the large “community” union building in any way, mind you, the BU cops rushed in and started violently arresting Southern Africa Task Force members. Eleven of us were handcuffed and driven to the Area D Boston Police station. The BU administration said in a Daily Free Press article of April 30, 1986 that its cops arrested us “for interfering with the efforts of B&G (Building and Grounds) workers to dismantle the structure (sic, I believe we built at least two structures) and for physically obstructing police cruisers on Commonwealth Ave.”

The Boston Police at first refused to formally book us or lock our cells, telling the BU police that the city of Boston had fully divested from South Africa and we hadn’t done anything wrong (“a real bunch of criminals you’ve got here,” I recall one of them saying to BU cops). So a BU police lieutenant went cell to cell with a Polaroid and “booked” us. Eventually the BU administration managed to get us charged. Hours later our supporters paid our bail and we were released on our own recognizance.

John Silber and his administration waited until June, when most students were on summer break, to hold a kangaroo court of (again) handpicked students, faculty, and administrators empowered to judge us under the Code of Student Responsibilities (formerly the Code of Student Rights and Responsibilities that the Silber administration had unilaterally changed to eliminate all student rights in campus disciplinary proceedings) that the other 10 members of the “BU 11,” as we came to be called, and I were not allowed to attend. Naturally, we were all found “guilty”—despite the fact that the city of Boston hadn’t processed our misdemeanor cases yet and later dropped all charges against us.

Two members of the BU 11 had their degrees withheld until January 1987, the equivalent of a suspension, according to the hilarious September 1986 bu exposure article on our arrest by fellow arrestee Eileen Eckert. One got disciplinary probation until graduation (under which you’d get in worse trouble if you were dinged for even the tiniest infraction dreamed up by the Silber administration). Two got disciplinary probation until January 1987. Five were suspended until January 1987. And Eileen got this wrong since I was no longer at school when she wrote her piece, but I was given the worst sentence: One year of suspension plus disciplinary probation until graduation should I ever manage to return to BU—supposedly because I had been briefly arrested by BU police (and internally cited by the administration) at another protest that spring.

But my “judges” knew perfectly well that I would not be returning. Because the worst punishment the administration hit me with was done completely on the quiet. They rescinded my half scholarship without comment. And I don’t come from money. A fact of which they were well aware.

The Silber administration, to conclude my reverie, expelled me. For participating in a completely nonviolent student protest capping off a long series of similar protests. After using the puppet leaders of the BU Student Senate, where I was on the verge of getting a majority of senators to come out in favor of our university divesting its South African investments (and possibly even declaring ourselves to once again be an independent student government), to throw me out as one of two senators from the College of Communication in violation of Senate bylaws midway through my final school year. Not long before getting the top editors of the main (nominally) independent student newspaper, the Daily Free Press, to remove me as a very junior editor and columnist—having threatened to stop buying ads representing the majority of the paper’s budget should they fail to do so.

And these actions against me were a result of what exactly? More high spirits and more low-level functionaries operating without authorization?! No. If one understands anything about Boston University between 1971 and 2003, it is that its administration was John Silber. Nothing of any consequence happened on that campus without his ordering it or at least signing off on it.

So Rachel Silber Devlin will forgive me for stating that her view of her father’s attitude toward protest at the university he ran with an iron fist is a complete fantasy from the perspective of those of us who actually did it.

In my opinion, informed through extremely direct personal experience as it is, John Silber did not want protest of any kind at his university, if he didn’t agree with it. And he rigged the system he controlled from top to bottom to prevent students, staff, and faculty with views at variance with his from exercising our rights to freedom of speech and freedom of assembly, not to encourage them. That thousands of BU community members, some of whom I hope will join me in taking the time to publish their experiences* in the weeks to come, did so anyway underscores their tenacity in defense of those core democratic tenets, not Silber’s munificence.

Nearly thirty-seven years later, I have never received so much as a back-channel, unofficial apology of any kind—let alone remuneration for all the money that my parents and I spent for my two academic years as a student with no diploma to show for it or, god forbid, an honorary degree—from Boston University. In recognition of the real harm they did to me and my family.

For all that, I do forgive John Silber. I remember having been planning to visit him if he was willing to see me, when the news came that he had passed away. Which is a shame because I would really have liked to get his perspective on the events I just recounted. Since I owe him a debt of gratitude for teaching me the real value of reasoned debate in our failing democracy … whether he meant to or not.

*BU community members who protested against the Silber administration are welcome to contact me at jason@binjonline.org, if any of you would like the Boston Institute for Nonprofit Journalism to publish opinion articles about your experiences.

Apparent Horizon—an award-winning political column—is syndicated by the MassWire news service of the Boston Institute for Nonprofit Journalism. Jason Pramas is BINJ’s executive director, editor of the Somerville Wire, executive director of the Somerville Media Fund, and executive editor and associate publisher of DigBoston.