Please share this information widely

Jason Pramas

A Home in the Digital World

crisis

‘WALK THE TALK’

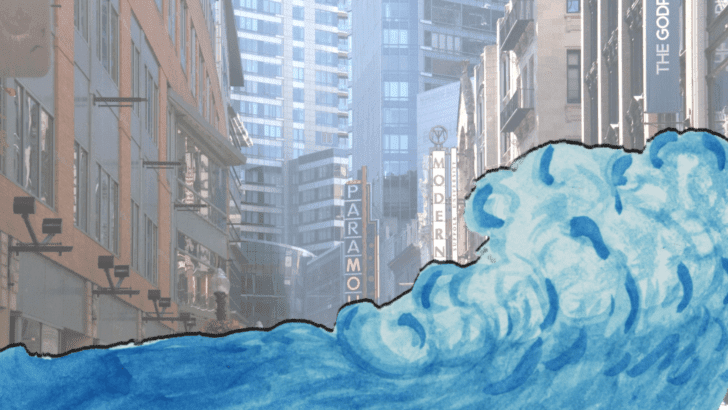

Mayor Walsh needs to act faster to mitigate regional global warming threats

June 13, 2018

BY JASON PRAMAS @JASONPRAMAS

Environmental groups protested Mayor Marty Walsh last week during the International Mayors Climate Summit and subsequent US Conference of Mayors meeting—demanding fast action to make Boston carbon neutral (achieving net zero CO2 emissions) and better prepare the city for the many threats to the region from the already-visible effects of global warming. Like the two “once in a generation” storms this winter that both quickly flooded our waterfront.

According to WGBH’s Greater Boston, “The good news, for advocates who think the city is falling short, is that Walsh says he welcomes public pressure in this area—and that big changes to the way the city operates are coming. Soon.”

The bad news, of course, is that pols can say anything they want. But are unlikely to act until their feet have been held to the fire. So, kudos to area climate activists for continuing to do that.

Interestingly, the summit was scaled down from a huge confab that would’ve hosted thousands of public leaders from the US and China in 2017 to a smaller 2018 conference that featured “20 US mayors and four officials from cities in other countries, including China,” according to the Boston Globe.

Walsh is doubtless happy to blame the election of the Trump administration for the lack of State Department support for the conference leading to a year’s delay and the lower turnout. Democrats like himself and former Secretary of State John Kerry—who originally announced Boston summit plans in Beijing in 2016—are getting a lot of political mileage out of poking holes in Trump’s slavish support of the oil, coal, and natural gas industries that are directly responsible for global warming. While pointing to his pulling the US out of the Paris climate accord by 2020 as tantamount to ecocide.

Unfortunately, the Democrats have been no less slavish in their support of the oil, coal, and natural gas industries at every level of government. And the Paris agreement is perhaps the best example of that slavishness.

Because the Paris climate accord is voluntary. So, even in countries that ratify it, the treaty can’t force the fossil fuel industries and the governments they often effectively control to do anything. No surprise there, since the process that launched it—the annual Conference of the Parties of the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change—allows fossil fuel corporations to participate in everything from funding its meeting sites to directly influencing its negotiations and implementation rules, according to 2015 and 2017 reports by Corporate Accountability International (CAI, formerly INFACT). An advocacy group that previously helped organize the Network of Accountability of Tobacco Transnationals—a coalition of mostly third world NGOs that helped exclude nicotine purveyors from the Framework Convention on Tobacco Control, a World Health Organization treaty process. CAI and its allies have repeatedly called for the fossil fuel industries to be similarly banned from participation in the negotiation of climate change treaties. To no avail, thus far.

One can certainly argue, and many do, that having even a voluntary treaty on global warming is better than not having one at all. But if multinational energy corporations like ExxonMobil, Shell, BP, Chevron, Peabody, and BHP Billiton were willing to voluntarily phase their fossil fuel lines out of existence, I would think that they would be well on the way to carbon neutral status by now. After all, most of them knew about the dangers of global warming decades back. According to a timeline by Climate Liability News, Exxon knew in 1977, Shell in 1988, and those companies and many others formed the Global Climate Coalition specifically to cast doubt on climate science in 1989.

Almost 30 years later, it seems foolish to bet on companies that make obscene profits by selling fossil fuels to suddenly have a change of heart and agree to stop making those superprofits.

Circling back to Boston, Mayor Walsh drew fire from groups like 350Mass and Mass Sierra Club last week on largely the same grounds. The city is not doing much more than drafting plans to implement mainly voluntary measures to mitigate the effects of global warming in the coming years.

It’s also working on those plans—formally and informally—with major corporations that play a variety of roles in worsening global warming. From investing in fossil fuel industries to developing environmentally unfriendly buildings. And it’s potentially underestimating the threat from global warming by choosing to ignore more dire climate models in its planning that are still well within the mainstream of climate science. City government is also not addressing all the major systemic “tipping points” under investigation by climate scientists that could conceivably affect the Boston area and their interrelation to each other. Focusing instead on three imminent threats: sea level rise, air temperature rise, and more intense storms.

Major planning processes on minimizing the risks presented to us by global warming are absolutely necessary and a difficult undertaking at the best of times. Yet there’s little sense that Boston’s developing climate plans are going to result in the policy pedal being pushed to metal anytime soon. Hence, last week’s protestors’ event hashtag: #WalktheTalkonClimate. The environmental groups made clear that we need Mayor Walsh and the rest of city government to take swift action to reduce the many threats from runaway global warming as much as any one city or region can… and do less talking about the need to take swift action.

That means divesting the city of all financial holdings in fossil fuel corporations. And moving on the Boston City Council’s resolution of last fall unanimously supporting “Community Choice Energy”—a plan that would allow Boston to join with other municipalities in buying energy in bulk on behalf of residents and small businesses. Enabling the city to mandate a higher percentage of renewable energy in such purchases. Then creating regulations with real teeth aimed at mitigating the many likely harms to our city from climate change.

For example, Boston (and the Commonwealth) can enact regulations that would force developers of the millions of square feet of new building projects sprouting up around the city to prepare for flooding from global warming-induced sea level rise. Especially new construction in the city’s now massively overdeveloped waterfront. Hub solons can also pass regulations that would compel those same developers to power new buildings with genuinely renewable energy (i.e., not natural gas or nuclear). And regulations that would also make such buildings as energy efficient as possible.

Beyond that, the city should get going on actually building flood defenses and neighborhood cooling centers; and pressing ahead with operationalizing other big ideas currently under discussion in various city planning processes. Or outside of them in my case—as with my support for moving key city infrastructure to higher ground at speed, and eventually moving the seat of Massachusetts state government to Worcester.

Ultimately, properly preparing the city to deal with the negative effects of global warming is everyone’s job. Because politicians can’t do it all themselves. Nor should they. So, readers should contact the mayor’s office regularly to demand faster action on the issues mentioned above, participate in relevant public hearings and meetings to make your voices heard, and get active with any of the environmental organizations large or small that look to be fighting hardest in the public interest.

Just remember, Bostonians failing to be vigilant can result in city government dropping the ball on even fairly straightforward climate-related promises. Like former Mayor Thomas Menino’s plan to plant 100,000 new trees by 2020. As of this month, there’s been a net gain of 4,000 trees since the initiative was announced a decade ago.

In the same period, New York City promised to plant 1,000,000 new trees by 2017. And reached that goal two years early. They’re also well ahead of Boston with global warming preparations.

Worth considering why that might be. Before the next mayoral election.

TOWNIE: CITY ON A HILL

Global warming will flood Boston. Why not move the state capital to Worcester?

May 26, 2018

BY JASON PRAMAS @JASONPRAMAS

Many small American cities have boosterish metro research organizations that look like a cross between a public policy outfit and a chamber of commerce, and the Bay State’s second biggest urban area is no exception. The Worcester Regional Research Bureau (WRRB) was founded in 1985 during a period when all of Massachusetts’ major cities were facing a funding crisis caused by the tax-slashing Proposition 2 1/2 and needed to find ways to keep their local economies functioning with less funding from state government. Since that time, according to its website, the “Research Bureau has prepared over 220 reports and held over 200 forums on topics including public administration, municipal finance, economic development, education, and public safety.” Its board is like a who’s who of the Worcester power structure.

In March, WRRB released a 10-page report, “Brokering a New Lease: Capturing the Value of State Offices for Massachusetts.” Not exactly the kind of title that’s going to inspire headlines, and it didn’t—only receiving coverage in the Worcester Business Journal and Commonwealth magazine. But the white paper actually makes an interesting point: Why are the headquarters of the many state agencies mainly in the Hub?

Boston has very expensive real estate prices. And even though the state owns some office buildings around town, many agencies lease commercial space for their headquarters. So, WRRB reasons, wouldn’t it make good sense to move some of those HQs to Worcester? Saving the Commonwealth money, and helping the Worcester economy with lots of decent state jobs in the process?

Consider that, according to the report, Class A office space in Boston was running as high as $60.85 per square foot in 2017. It then points out that the “state pays an average of $37 per square foot across its Boston lease agreements, with a high of $73 per square foot near Boston City Hall and a low of $19 per square foot in Hyde Park.”

Meanwhile, “Brokering a New Lease” continues: “The [WRRB] consulted the City’s Economic Development Office and local real estate brokers and identified 275,000 square feet of available space across eight buildings that could feasibly house a state office. … The average rent was $21.31 per square foot, and one local broker said $22 per square foot would be a reasonable minimum estimate for new leases involving capital investment.”

A savings of $15 per square foot on average—which translates to my back-of-the-envelope estimate of $4,125,000 a year that would stay in the Commonwealth’s coffers—is nothing to sneeze at. It’s true that removing 275,000 square feet of the 1,675,806 square feet that the state currently has under lease in Boston, according to the report, would mean that the Hub stands to lose 16.4 percent of its state office space. Not an inconsiderable economic hit for Boston’s commercial real estate market, and something WRRB staff do not seem to be concerned about. But Worcester’s gains would potentially offset Boston’s losses from such a deal, when considering the state economy in its entirety.

Which makes the report’s rationale for moving some agency offices sound reasonable on cost-benefit grounds alone—although I can understand why many state employees might not want to move from more cosmopolitan Boston to a city with less social and cultural opportunities on offer. On the other hand, with a significantly lower cost of living, state salaries will stretch a lot further in Worcester County. To the point of allowing low-level bureaucrats, who couldn’t dream of buying so much as a condo in Boston these days, to buy a house out there.

But what interests me about the report is not so much its original subject as something I’m sure that WRRB staff hasn’t yet given the slightest thought. Over the last few years, I’ve written numerous columns and editorials sounding the alarm about what I feel is Boston’s woefully inadequate preparations for the several major global warming-induced crises that scientists expect coastal cities to endure in the coming decades. One of the most dangerous of those is sea level rise. Much of Boston is low-lying former wetlands, and unless we start building major harbor-wide flood defenses soon, we don’t have a prayer of slowing the Atlantic Ocean’s reclamation of those areas. And doing grave damage to critical systems like power, transportation, and sewage in the process.

Even if Boston does build huge dikes, and make other needed changes to the city design, it’s only a matter of time before the ocean wins. Since sea levels are expected to continue to rise for hundreds of years until, potentially, all of Earth’s major land-based ice sheets have melted into the ocean.

So why not move the state capital to Worcester—a city whose elevation is 480 feet—in stages? Starting with getting state agencies out to the city appropriately nicknamed the “Heart of the Commonwealth” in the manner the WRRB suggests. Then building the bullet train to Boston that former gubernatorial candidate Setti Warren is so excited about. And gradually transferring more and more of state government to the “City of Seven Hills” (the place really has a lot of nicknames). Until, eventually, we move the State House itself.

In addition to helping state government better weather global warming, having our capital in the middle of the state could go a long way toward healing the many divisions between eastern and western Massachusetts.

Don’t get me wrong; this is not the kind of proposal I’d make if we weren’t facing climate change dire enough to threaten the survival of the human race. But we are. Not today. Not tomorrow. Someday soon, though. We’re already seeing signs and portents now in the increasingly frequent “wild weather” that dishonest meteorologists like to prattle on about on Fox and its ilk. Including Worcester becoming more of a tornado alley than it already was—something I don’t think is nearly as much of a threat as the anticipated 10 feet of sea level rise Boston is facing by century’s end. More, if the land-based Greenland and Antarctic ice sheets start sliding into the ocean faster than the majority of climate scientists are currently projecting.

In past writing, I’ve suggested moving critical Boston infrastructure to the hills in and around the city. We will still need to do that. But growing Worcester while shrinking Boston is another smart move to consider. And why stop at just moving the state government? Why keep the city’s population exposed to ever more fierce hurricane- and winter storm-driven flooding when we can gradually move to a nearby city that could absorb quite a lot of our population before reaching capacity? A city acceptably far from the sea and major river systems, and high enough to not have to worry about being permanently flooded out (except, perhaps, in the worst possible scenarios).

Anyhow, food for thought. I’d be curious to hear what the WRRB staff—and other policy wonks and urban planners in “Wormtown” (loving these nicknames)—think about my proposal. I make it in earnest, and hope it is taken in the spirit with which I offer it. They can reach me, as ever, at jason@digboston.com.

Townie (a worm’s eye [ironic, no?] view of the Mass power structure) is syndicated by the Boston Institute for Nonprofit Journalism. Jason Pramas is BINJ’s network director, and executive editor and associate publisher of DigBoston. Copyright 2018 Jason Pramas. Licensed for use by the Boston Institute for Nonprofit Journalism and media outlets in its network.

THERE WILL BE NO OUTSIDE WORLD TO HELP US

Boston’s global warming plans must prepare region for worst case scenarios

March 28, 2018

BY JASON PRAMAS @JASONPRAMAS

In a couple of recent columns—and several others over the years—I’ve looked at some of the specific threats that scientists expect Boston will be facing from global warming-induced climate change. While there’s plenty of room for debate about the anticipated severity and timetable of such threats, there is no longer any serious doubt that they are real.

Unfortunately, humans have trouble dealing with existential crises like an inexorably rising sea level and the relentless increase of the average air temperature.

We tend to try to plan for future situations based on what has happened in the past. What is, therefore, in the realm of our experience as individuals and as members of various groups. What we’re comfortable with and confident we can handle.

The many learned experts who have been working on the city of Boston’s various climate change initiatives are no less susceptible to this bias than anyone else.

Which is why the reports city government has been producing on making the city more “resilient”—to use the fashionable buzzword pushed by the Rockefeller Foundation and others of late—in the face of climate change all share a major flaw.

That is, despite understanding that global warming is by default—by its very nomenclature—a worldwide phenomenon, they treat the effects of the climate change it’s driving as essentially local.

Furthermore, they try to apply standard disaster preparedness and emergency management protocols as if global warming was simply a series of tractable crises of the type we’ve dealt with since time immemorial. Like the recent series of nor’easters (which were probably climate change-driven themselves).

So, sure, they reason. There will be power outages—some affecting critical infrastructure—so we’ll plan for that. There will be food shortages in some poor areas of the city that are already considered “food deserts” due to their lack of decent cheap supermarkets; so we’ll plan for that. There will be flooding; so we’ll plan for that.

Thus, the language that city officials (and an array of outside advisors and consultants) use in their climate change planning documents demonstrates that they’re either unable to see that previous human experience is insufficient to the task of grappling with global warming… or, more likely, that they’re unwilling to discuss the vast scale and centuries-long duration of the approaching crisis due to a combination of factors. Ranging from not wanting to be seen as alarmists to not wanting to anger top politicians and corporate leaders with big problems requiring expensive solutions.

For example, here’s an illustrative passage from the Climate Ready Boston Final Report, the big global warming preparedness white paper the city published in late 2016:

Members of the IAG [Infrastructure Advisory Group] have identified continued functionality of the city’s transportation infrastructure as a top resiliency priority. Many members have identified road and bridge functionality as a key critical requirement so citizens can evacuate; emergency vehicles can pass; maintenance trucks can reach impacted electric, communication, and water/wastewater assets for swift repair; and hospitals and other emergency facilities can continue to receive food, water, and medical supplies. In turn, the transportation system relies on continued access to electricity and communications systems, so tunnels may remain open, and any blocked paths are cleared quickly or detours swiftly communicated.

Note that it’s assumed that citizens will be able to evacuate the city if necessary. And that various kinds of critical vehicles will have fuel. And that parts will be on hand for infrastructure repair. And that food, water, and medical supplies will be available.

Climate Ready Boston’s series of reports and a raft of related studies certainly mention a variety of problems that the city will have to overcome to ensure that fuel, food, water, medical supplies, vital machine parts, etc. will be available as locals recover from each new storm, flood, or heat wave. Like making sure that Route 93 is no longer the main trade route for the city and that the portions of the highway that are susceptible to flooding be reengineered.

And they definitely allow for the fact that we’ll see more and more storms, floods, and heat waves.

But none of the growing array of reports and plans that city (and also state) government are producing consider this possibility: That at a certain point—especially if we continue along the climate change denial path that the Trump administration and the oil, gas, and coal industries are setting us on—Boston will be alone.

There will be no outside world to help us. Every city, every region, every nation on the planet will be engaged in a life-or-death struggle for survival as the effects of global warming get worse. And worse. And ever worse.

Because maybe humanity does not stop burning carbon in time. Because we do not replace our old dirty energy systems with new clean ones. Because we do not halt the despoiling of land, sea, and air. Because we do not reverse the “sixth extinction” of most species of plants and animals. Because we do not, in sum, stop the destruction of the human race itself and everything that matters to us in the world.

Hopefully, things won’t be so bad by 2100—which is the outer limit of the period seriously considered in city and state plans. Let alone in 20 or 30 years. But the minimal progress on climate change goals that have been made in the quarter century since the Kyoto Protocol was signed does not inspire confidence in human civilization’s ability to reduce greenhouse gas emissions enough to slow—let alone stop—the worst-case scenarios that keep any reasonably well-informed person up at night.

So if the city and the state that surrounds it want to talk about “resilience,” they have to be able to answer these questions… and many more like them besides:

✦How will Boston (and Massachusetts) feed our already-growing population—when global supply chains are disrupted and ultimately destroyed, the oceans are dead, and much of America’s farmland has turned to dust bowls—given that we can’t even come close to feeding ourselves now? And what about all the climate migrants that will be heading north as parts of our continent become uninhabitable? How will we possibly feed them?

✦How will Boston (and Massachusetts) keep our growing population plus climate migrants clothed, housed, healthy, and gainfully employed in that situation?

✦How will Boston (and Massachusetts) produce enough clean (or dirty) energy to satisfy our growing power needs—including our vehicles—without outside help?

✦How will Boston (and Massachusetts) produce the manufactured goods that we need—including medical supplies and the materials we’ll need to rebuild during a never-ending series of global warming-induced disasters—when we’re on our own?

✦How will Boston (and Massachusetts) grow more food, support more population, and expand industry in the coming decades as we face the expected global warming driven fresh water shortages? Even as we grapple with more and more severe floods due to storms (fresh water), and storm surges (seawater).

✦How will Boston (and Massachusetts) move the city, our state capital, and its critical infrastructure to higher ground—while buying time to do so with the best possible flood defenses we can build?

✦How will Boston (and Massachusetts) help the entire population of the city to move to relative safety when global warming-induced climate change eventually makes our region uninhabitable, too?

Any planning process that fails to raise such questions is not worthy of the name. So both the city of Boston and Commonwealth of Massachusetts had better step up their joint game… fast. Same goes for climate action groups that work hard to keep grassroots pressure on responsible government officials (and generally irresponsible corporate leaders). Work harder, grow your ranks, pursue mitigation efforts that might forestall the worst outcomes, become an unstoppable force, make positive change at least a possibility. If not a certainty.

Because if we can’t stop (or significantly slow) global warming, and we can’t find practicable answers to the above questions soon, then Boston is far from “resilient.” Let alone “strong.” It is completely unprepared to deal with global warming-induced climate change.

And all the reports in the world won’t save our city and our state from the grim fate that awaits us.

Apparent Horizon is syndicated by the Boston Institute for Nonprofit Journalism. Jason Pramas is BINJ’s network director, and executive editor and associate publisher of DigBoston. Copyright 2018 Jason Pramas. Licensed for use by the Boston Institute for Nonprofit Journalism and media outlets in its network.