Four votes against the proposed leasing of city parking spaces should do the trick

Oftentimes when covering a public meeting, journalists like myself will feel like we’re in the same boat as the rest of the audience. Because much of the discussion is new information for everyone. So we don’t feel like total outsiders.

But that was not the case when I attended the “Town Hall Meeting relative to the disposition of the state-owned Sullivan Courthouse” at Kennedy-Longfellow School in East Cambridge last Thursday evening. The specifics of the matter at hand were fairly new to me. Yet for many of the 125-plus neighborhood residents that showed up, the event was like going to a bad horror movie for the 20th time. They’d heard everything under discussion before. And wanted nothing so much as to never have to attend such an affair again.

State Rep. Mike Connolly (D-Cambridge) called the meeting. But explaining why he did so will require me to run readers through a fast review of one of the longest policy battles in Cambridge history.

What has gone before

East Cambridge residents never wanted the Edward J. Sullivan Courthouse. It was dumped on them by the now-defunct Middlesex County government, which used its immunity from local zoning laws to open what is universally considered to be a 22-story brutalist concrete eyesore in 1974. Bankrolling it with its own funds—which likely played a role in the county’s eventual insolvency and its abolition by the Commonwealth of Massachusetts in 1997.

Abutters and the neighborhood at large were not consulted about the building. And the almost immediate protests by the same generation of locals that defeated the infamous “Inner Belt” plan that would have driven a major highway right through Cambridge fell upon deaf ears. That turned out to be merely the first act of a saga that has dragged on to this year and has seen East Cambridge residents repeatedly ignored and abused by the city, county, and state governments that are supposed to represent the people’s will.

Unsurprisingly, the courthouse was poorly built, and by 2008 state government—having inherited the structure in 1997 and refusing to properly repair it or to remediate the massive amounts of toxic asbestos found within—decided to move the Middlesex Superior Court staffers who had worked there to a new facility in Woburn. Leaving over 200 prisoners in the top four floors to languish there, nearly forgotten, until 2014, according to the Cambridge Chronicle. The Commonwealth then offered the building to the City of Cambridge.

Here was an opportunity for democracy to reign at last. East Cambridge activists encouraged the city to buy the courthouse, pay to remove the asbestos, level it, and then pursue new public development on the site with proper community input. But instead, on May 25, 2010, both the powerful unelected City Manager Robert Healey and the less-powerful elected City Council declined to buy the courthouse from state government, according to the Boston Globe. Never giving serious thought to the good the city could do by taking the site over. Yet another nail in the coffin of the myth of the supposed “People’s Republic of Cambridge.” Believed these days only by suburban reactionaries that rarely set foot in the city.

This led the Commonwealth’s Division of Capital Asset Management and Maintenance (DCAMM) to put out a request for proposals from commercial developers to purchase the building in November 2011. In February 2012, eight developers did so. In March 2012, DCAMM rejected all the proposals on vague grounds, according to the Boston Business Journal. The agency then put out another call for bids. This time seven were accepted. The most popular of which was fielded by HYM Investment Group—the developer of nearby Northpoint, led by former Boston Redevelopment Authority honcho Thomas O’Brien—and called for a mixed-use building that included a good deal of housing.

However, in December 2012 DCAMM accepted the proposal by Leggat McCall Properties (LMP) that called for the entire structure to be used for office and commercial space, according to the Boston Business Journal. And unlike the HYM proposal that had promised to take four floors off the top of the building, the LMP proposal did not. This caused a huge uproar in East Cambridge. Which saw repeated actions and meetings involving hundreds of people throughout 2013 and much of 2014 aimed at stopping or modifying the winning bid.

Neighborhood activists appealed to every government body they could think of without success—up to and including then-Gov. Deval Patrick, who rebuffed them in April 2013, according to the Boston Business Journal.

In the first few months of this period, LMP tweaked its initial proposal to include 24 units of housing and make a number of cosmetic changes to the building facade. Meanwhile, the developer had already signed a purchase and sale agreement with DCAMM on Jan 16, 2013, and an important license agreement on March 11, 2013.

Then in 2014, according to the Cambridge Chronicle, former State Rep. and longtime City Councilor Tim Toomey formed a working group “with 18 representatives from both the Neighborhood Association and the Planning Team, along with abutters and business owners to work with Leggat McCall on mediating their concerns.” The group succeeded in convincing LMP to remove two floors from the top of the courthouse and make more changes to its design.

One major issue in all the negotiations was that neither LMP nor DCAMM would tell anyone—elected officials like Toomey or Councilor Dennis Carlone, journalists from publications like the Chronicle, or community groups like the East Cambridge Planning Team—how much the developer had offered the state for the contested property. Leading a number of those parties to file public records requests with the Commonwealth. LMP had indicated that building out its proposal would cost it $200 million, but neither party to the deal would indicate what its bid price was—or what DCAMM’s specific process for choosing LMP over other developers was.

Despite this lack of critical information, both the state and the city steamrolled the process along. According to a city manager’s order of Oct 7, 2013, the City Council voted that day—at the behest of City Manager Richard Rossi, as indicated in his letters to the council of Oct 7, 2013, and March 24, 2014—to “make available for disposition a long-term leasehold interest to Leggatt [sic] McCall of four-hundred twenty (420) parking spaces and a portion of the ground floor retail space at the City-owned First Street Garage.” A move that was made specifically to provide LMP the parking spaces it needed to legally complete the courthouse deal. Another point where more thoughtful action by Cambridge city government could have resulted in the restoration of public control of the Sullivan site.

This began the “parking disposition” process, which has yet to be resolved. According to city ordinance 2.110.010 (Disposition of city property), section F. “The disposition of City property shall require a 2/3 vote of the City Council.” Stick a pin in that fact for a moment. The fate of the entire LMP proposal now rides on that council vote.

For much of 2014, the Cambridge Planning Board issued the necessary series of special permits to allow LMP to start work on its courthouse project—over vociferous protests by East Cambridge residents.

The first attempt to issue the final permits came on July 29, 2014, at a special planning board meeting at the Kennedy-Longfellow School auditorium. So many people showed up to testify according to the official transcript (Page 210)—overflowing the space’s capacity—that the public comment period went on too long for the board to discuss the matter and it postponed its decision for two months.

Finally, at a Sept 30, 2014, meeting at the same location, the Cambridge Planning Board approved the last permits, according to the Cambridge Day.

Just a few days later on Oct 3, 2014, according to a document on Councilor Toomey’s website, after Toomey appealed to the secretary of the Commonwealth to force DCAMM to produce public records pertaining to the LMP courthouse deal—including the sale price for the facility, and “the bid selection process and criteria that were used by DCAMM in selecting Leggat McCall Properties as the developer for the courthouse”—the supervisor of records ordered the agency to release them.

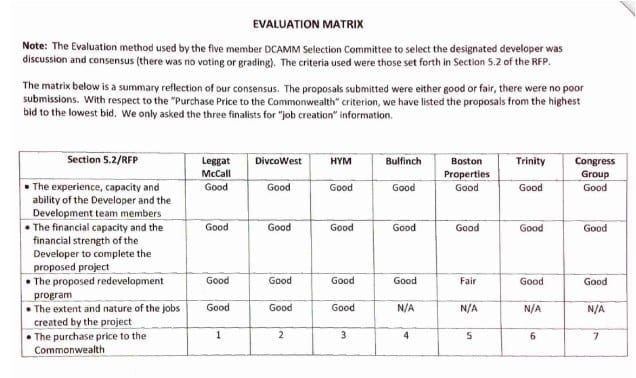

By Oct 23, 2014, Toomey had all the records and put them on his website. They showed that LMP had bid $33 million for the property, that the main criteria for DCAMM’s selection of the LMP bid was that it had offered more money than the other six developers, and that community concerns were not factored into DCAMM’s “evaluation matrix” (see accompanying graphic) at all.

Infuriated neighborhood activists followed through on their threat to file a lawsuit in Land Court to stop the LMP project—on the grounds that the government immunity that Middlesex County had used to build a courthouse and jail was now void, and that normal zoning restrictions should be applied. Which would kill the deal. That court shot down the suit in 2015. The plaintiffs then took their case to the Massachusetts Appellate Court. And were defeated there in 2017, according to the Boston Herald.

In 2018, the city returned to the long-stalled parking disposition process to give LMP a 30-year lease to the 420 city parking spaces—out of a total of 1,100, over 500 of which are already leased by other companies (a big sticking point with the community)—that it needed to complete the project.

On Oct 30, 2018, the city called a meeting at the Multicultural Arts Center to discuss moving forward with the parking vote by the City Council. And a massive turnout against the project convinced Rep. Connolly to call last week’s meeting.

Two ways forward

Said meeting made one thing quite clear to me: The neighborhood is sick of the courthouse fight. To the point where some residents who fought hard against the LMP proposal are now willing to go along with it. If for no other reason than to ensure that the abandoned building—that’s apparently been without power for weeks, and not for the first time—doesn’t fall further into disrepair. With potentially significant environmental and health consequences.

However, if the cheering (and often, quite pointed jeering) by the various factions—LMP detractors, LMP supporters, and people who just want something to be done with the building fast as long as it doesn’t remain the way it is—is any guide, the activists against the current courthouse plan remain in the majority. And it was to those people and fence-sitters that Rep. Connolly tailored the event.

Together with longtime neighborhood activists who provided ample historical context, the representative presented a proposal for a very different—and far more democratic—development process than anything that has gone on in East Cambridge since the courthouse was forced on the community a half-century back.

Connolly’s office produced a 10-page document for the meeting entitled “Toward a Community-Driven Framework for the Public Reuse of the Sullivan Courthouse Site.” It’s available online at tiny.cc/CommunityDrivenFramework. The goal of the framework, as presented and debated at the meeting, is to essentially hit the restart button on the entire courthouse development initiative.

As Rep. Connolly explained his thinking last Thursday and reiterated to me in a subsequent conversation, everything hinges on the City Council vote on the disposition of the 420 parking spaces in First Street Garage. Which may (or may not) happen as soon as June.

If the council fails to get six out of its nine members (two-thirds as per the above cited disposition ordinance) to vote in favor of granting a 30-year lease of those spaces to LMP, then the entire courthouse deal with the developer likely falls apart. Because the facility only has 92 parking spaces onsite and needs 420 more spaces within 1,000 feet for the LMP plan to move forward. Four votes therefore are probably all that are needed to defeat both the parking lease and the overall plan.

According to the framework document, “From there, the City, working in partnership with residents and state officials, would want to advance, further refine, and formally adopt a Community-Driven Framework that would establish development objectives, implementation options, and a process for negotiating with DCAMM and the Baker Administration for either the direct acquisition of the Courthouse site or a new bidding process subject to community-driven objectives.”

This can happen because the latest extension to the January 2013 purchase and sale agreement between DCAMM and LMP expires in December. In all these years, LMP has never actually closed the sale on the courthouse and paid the state the full promised $33 million—although they have paid a few million in deposits and fees. There are project supporters currently insisting on social media that a purchase and sale agreement is somehow sacrosanct. But such agreements expire all the time. So that doesn’t seem to be a very strong argument.

Once the clock runs out the agreement, the hope of Connolly and project opponents is that DCAMM will follow through on what its staffers told him last fall after the Oct 30 public meeting, and “re-evaluate the current process and look to begin a new disposition process.” During which Cambridge could have a shot at negotiating with the state for the “public reuse” of the courthouse site. Project supporters online have also talked to DCAMM officials. Who look to be trying to walk back their earlier statements to Connolly—which he entered into the city record by emailing them to the council, city manager, and city clerk immediately after talking to DCAMM. But those officials have not yet denied that renegotiation of the deal is a possibility. Unsurprising, since they’ll have to revisit the deal one way or the other if LMP can’t get the parking spaces it needs.

Naturally, if the council votes to approve the First Street Garage parking disposition, then the hotly contested courthouse plan will be built at last. And still-strong community opposition be damned.

LMP, for its part, aside from mounting a last-minute charm offensive by opening a PR office for the project on Cambridge Street and planning to canvass the neighborhood in support of its bid for the First Street Garage lease, is doubtless putting pressure on city councilors behind the scenes to vote its way. I visited the office just prior to writing this column, and spoke to two nice young staffers who told me that the company has no plans to hold its own community meetings. I also took the project handouts on offer and noted that LMP now brags about the very changes to its proposal that it was pushed to accede to by community action in 2013 and 2014.

Given the choice between the highly compromised and undemocratic business-as-usual option in the form of the LMP project, and the democratic Community-Driven Framework for the courthouse proposed by Rep. Connolly and East Cambridge activists, I think the choice is clear: Cambridge readers should call or email every city councilor immediately and tell them to vote against the First Street Garage parking disposition—allowing the Community-Driven Framework a shot at finally giving East Cambridge residents the courthouse project that they deserve.

One fully in keeping with the intent of developer Andrew Craigie 206 years ago, according to the 40thorndike.org website, when he gave the contested site “‘to the people’—for the ‘sole purpose’ of building a courthouse, a ‘gaol,’ and other buildings that promoted a public, civic use, and ‘for no other purpose whatsoever.’”

At the moment, two councilors are likely to vote against the First Street Garage lease: Councilor Dennis Carlone, a longtime opponent of the LMP project who attended last week’s meeting, and Councilor Quinton Zondervan, who sent an aide to the meeting with a statement saying “We have an opportunity to say NO, and I am committed to doing so when the parking disposition reaches the council.”

Only two other votes are needed to defeat the parking disposition vote, and I suggest that neighborhood activists and allies focus their lobbying efforts on Vice Mayor Jan Devereux, an environmental and community activist who is pretty good on development issues, and Councilor Sumbul Siddiqui, who was endorsed by the Boston chapter of the Democratic Socialists of America (and that’s your cue to act now, Boston DSA!).

For Cambridge residents who believe developers and multinational corporations have far too much power in the city, and that public land should be dedicated to public uses, this is a rare opportunity to win a major development deal for the people. To build desperately needed public housing and community spaces that the city is absolutely rich enough to afford. Or at least sell the property on much better terms for the neighborhood—not allow government agencies to auction it off for short money and tax levies far smaller than the vast treasure that will be made by those same companies when they flip the property for easy gain. Which LMP would be stupid not to do. Since, given recent giant real estate deals in Cambridge like last week’s leasing of three Osborn Triangle properties by MIT for $1.1 billion (at over $1,600 per square foot), according to the Boston Globe, it could take the $250 million or so that it will ultimately end up spending if the courthouse deal goes its way and can then sell it to another company for upward of $500 million. Imagine what kind of good that money could do if it was in community hands.

Democracy or oligarchy. It’s your choice, Cambridge residents. Here’s hoping you make the right one, and push your councilors to vote against leasing the First Street Garage parking spaces to Leggat McCall Properties.

Affected residents, organizations, labor and business leaders, and government officials are encouraged to send comments or opinion article submissions of 500-700 words on the Sullivan Courthouse situation to editorial@digboston.com.

Apparent Horizon—winner of the Association of Alternative Newsmedia’s 2018 Best Political Column award—is syndicated by the Boston Institute for Nonprofit Journalism. Jason Pramas is BINJ’s executive director, and executive editor and associate publisher of DigBoston. Copyright 2019 Jason Pramas. Licensed for use by the Boston Institute for Nonprofit Journalism and media outlets in its network.