Conglomerate’s woes throw Boston HQ deal contradictions into bold relief

November 15, 2017

BY JASON PRAMAS @JASONPRAMAS

What a surprise. General Electric is tanking, and the scheme to bring the multinational’s headquarters to Boston is looking worse by the day. And whom shall the public blame if that once-secret deal cut by Gov. Charlie Baker and Mayor Marty Walsh in January 2016 goes south? Potentially tossing away millions in tax breaks and direct aid to a company that has already done massive damage to the Bay State over the past few decades? Readers of the dozen columns I’ve written criticizing the boondoggle will already know the answer to that question. But for those of you who have made the mistake of believing all the massive amounts of PR bullshit that the Boston Globe and other area press have been tossing around about the affair since that time, here’s a bit of a recap.

Where to begin? So, the governments of Boston and Massachusetts agreed to shovel tens of millions of dollars at GE in “exchange” for “800 jobs” in a new corporate headquarters campus in the Fort Point district of the Hub. Many of which would simply be transferred from the old headquarters, and most of which would be executive level jobs that will not help Boston’s struggling, underemployed working class.

Now there’s a problem. GE’s been losing money all year. According to the New York Times, its stock price had already dropped by 35 percent since January. Then, according to CNBC, the company’s share value dropped another 13 percent this week as of this writing after new CEO John Flannery announced a restructuring initiative—including the one thing investors hate most of all: dividend cuts. Only the second for GE since the Great Depression. So the knives are coming out around the beleaguered behemoth, and it remains to be seen whether some internal reorganization (doubtless costing legions of employees their jobs) and some belt-tightening by its execs will be enough to stop investors from moving to carve the conglomerate up like a Thanksgiving turkey. But let’s not assume the worst just yet.

Funny thing about that belt-tightening, though. According to the Boston Herald, cuts are now in store for GE’s still-small local workforce, and construction of the new Fort Point headquarters building was already pushed back two years from 2019 to 2021 in August. The plan is to make do with the two old Necco buildings already being refurbished on the site at first. The PILOT (payment in lieu of taxes) agreement signed by the Boston Planning and Development Agency (formerly the Boston Redevelopment Authority) and the city of Boston guarantees up to $25 million in tax breaks to GE if it provides the much-ballyhooed 800 full-time jobs. But by what date?

The discussion around GE moving its HQ to Boston has focused on the corporation creating those jobs by 2024. Herein, then, lies the rub about the PILOT deal: The agreement is framed around GE hiring “approximately 800 employees at the Headquarters Building and the Necco Buildings within eight years of the Occupancy Date.” But that occupancy date is explicitly defined as “the date upon which the Company initially occupies the Headquarters Building.” Which has now been pushed back from 2019 to 2021, according to the Boston Business Journal. So 2024 cannot be the year that GE will need to have 800 employees on its new campus. 2027 would have been the earliest it had to meet that target. And now that’s been pushed back to 2029, given the delay with the headquarters building.

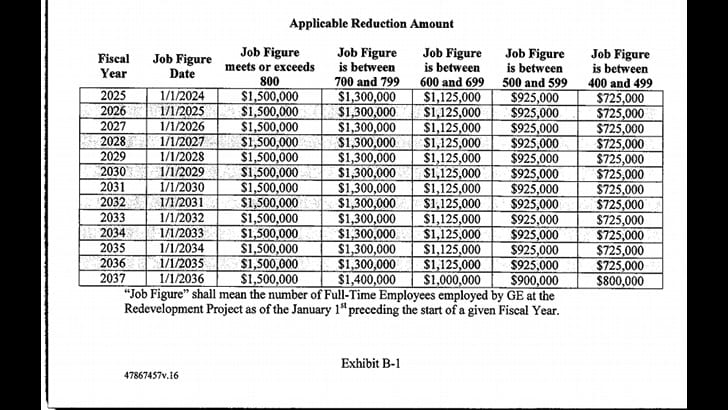

Yet it turns out that the PILOT agreement doesn’t actually require 800 jobs to be created. Remember, it starts by stating GE will employ “approximately” 800 people on the Fort Point campus. But further down in the document, in a table explaining the specific tax break the city will actually give the company during each year of the deal, it allows for the creation of as few as 400 jobs in a chart with five tax break tiers between “Job Figure is between 400 and 499” and “Job Figure meets or exceeds 800.” Keeping in mind that the agreement also specifies a “stabilization” period of seven years between 2018 and 2024, during which GE gets $5.5 million in tax breaks no matter what and isn’t required to provide any jobs at all for the first six years. GE is then only required to provide between 400 and 800 jobs from 2024 until the agreement ends in 2037.

What’s super puzzling is that agreement first requires the company to start providing annual job figures “from and after” the aforementioned occupancy date. But the agreement already established that it only really has to start meeting any job targets as far out as eight years from the date it occupies its headquarters building. Making the job target requirement trigger as late as 2029, according to current plans. Despite the tax break table in the PILOT agreement using job targets to calculate tax breaks beginning in 2025 based on the 2024 job count.

The state, for its part, committed a total of about $120 million to the project. Late last year, GE spent $25.6 million to buy 2.5 acres on the Fort Point Channel that includes the land the existing buildings sit on and the land the new headquarters building will (perhaps) one day occupy from Procter & Gamble. MassDevelopment, part of the Commonwealth’s economic development apparatus, took out a $90 million loan from Citizens Bank—an interesting maneuver worth looking into—using $57.4 million to purchase the two old Necco buildings on the site from P&G, and the rest to refurbish the buildings. The remainder of the state’s “investment” is slated to go to fixing up the area around the site.

So, GE is getting basically free rent on the Necco buildings plus free upgrades on abutting public land courtesy of the state. And a big chunk of the taxes it would normally pay over the next 20 years is coming free from the city. Without any real requirement that it actually provide any jobs in Boston for many years, and then only (maybe) 400 jobs by 2029—assuming the headquarters building is built in 2021.

Which is the problem with all such erstwhile “economic development” deals in the Bay State. From their origin as a way to help encourage investment in areas of the state that were down on their luck precisely because GE and companies like it moved their manufacturing operations away from cities like Pittsfield, Lynn, and Fitchburg to places without the decent labor and environmental regulation that was in place by the 1970s, they have become yet another way for rich and powerful corporations to get richer and more powerful. Worst of all, such corporations hold all the cards in the deals. If they don’t get lavished with free public money, they can refuse to move their operations here or can leave if they’re already operating in the area. Once they get the cash they’re looking for, they can basically pull out at any time. Or as is the case with GE, they can “alter” the deal Darth Vader-style, leaving our local “Lando Calrissians” like Baker and Walsh to “pray” the deal is not altered “any further.”

The Boston Business Journal was correct to point out that GE will get $2.1 million in tax breaks on the Fort Point Complex by 2021—the year that the company now claims it’ll be completing its new 12-story headquarters building on the site. But what if it doesn’t build the new structure at all? It’s not clear. Because the PILOT agreement is pegged to job creation starting as far out as eight years after the headquarters building is built, and then allows for the company providing as few as 400 jobs between 2024 and 2037 rather than the 800 everyone’s been assuming. While not actually demanding any job creation until as late as 2029, making it unclear how the tax break will be calculated between 2025 and 2029 should GE drag its feet for the full eight years. The conditions for the company defaulting on the agreement are also pegged to job creation. Not to the construction of the headquarters building. Oh, and by the way, the PILOT deal only covers the headquarters building and the land the company purchased under and just around it (which the agreement calls the “Headquarters Project”). Not the Necco buildings, now owned by the state. Also, there’s no word about what happens if the company has less than 400 workers in Boston at any point from 2024 to 2037. Do these curious contradictions amount to loopholes for GE to bag the whole deal? It certainly looks that way.

The minimum GE will get in tax breaks from the city of Boston over 20 years is $5.5 million by 2024 plus whatever breaks it qualifies for between 2025 and 2037. However, the amount the company actually puts out in annual PILOT payments after 2024 is calculated by a complicated formula based on the taxes that would have been assessed without the PILOT agreement. And the assessed value of the relevant property could change from current projections. So it’s hard to know what the total value of the PILOT deal will ultimately be to GE, other than that it will be a bunch of money… however many jobs it actually creates.

But why exactly are Boston and Massachusetts giving a huge company that’s still profitable any money at all? And what happens if GE bails on the scheme by hook (simply running and fighting its PILOT default in court with its vast legal department) or by crook (not building the headquarters building at Fort Point and possibly getting away with delaying the job creation target trigger until the deal ends in 2037)? And what happens if worse comes to worst for GE, and the company actually does collapse?

These remain my central questions. And I continue to encourage all of you to ask those and related questions to every Boston and Massachusetts politician you can find. And ask the Globe while you’re at it. They’ve got a loooot of ’splaining to do about their cheap boosterism… which they’ve become awfully quiet about of late. Preferring, it seems, to focus on the next giant company that’s demanding public bribes to come to town, Amazon.

A shorter version of this column appears in this week’s DigBoston print edition.

Apparent Horizon is syndicated by the Boston Institute for Nonprofit Journalism. Jason Pramas is BINJ’s network director, and executive editor and associate publisher of DigBoston. Copyright 2017 Jason Pramas. Licensed for use by the Boston Institute for Nonprofit Journalism and media outlets in its network.

![Students at rally at Boston City Hall by NewtonCourt (Own work) [CC BY-SA 4.0], via Wikimedia Commons](http://1fkoby17rlj41m4giv3x4cvk-wpengine.netdna-ssl.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/10/Students_at_rally_at_Boston_City_Hall_144819274-1.jpg)